Thermopylae—The Battle for the West vs. America: The Battle for Impeachment, Part III

“It is melancholy to record that only a very short time after this victory, which had temporarily united so many of the city-states of Greece, dissension between them all too soon began. Their brilliance, which still funds the whole of what is left of Western civilization, stemmed from their anarchic individualism.”

~Ernle Bradford

In reviewing Part II of my article series, based on author and historian Ernle Bradford’s masterpiece, Thermopylae: The Battle For The West, preparations for the Greco-Persian War revealed the sheer size of the Persian army and fleet—which greatly outnumbered the allied Greek forces—in addition to the wide array of weapons and armor of which the Greeks often surpassed the Persians, battle maneuvers (most famously the Spartan phalanx), and the strategic decisions exercised by key Greek commanders such as Themistocles in the face of insurmountable odds. Following the first encounters between both sides, and the actual warfare surrounding the most infamous and symbolic battle, Thermopylae. Fought between the 300 Spartans and 700 allied Thespians against the massive Persian army of 100,000-150,000 soldiers, Thermopylae was a valiant battle to the finish, and one representing the heroic final stand by King Leonidas against the persistent Persian land invasion. Now Part III, covers the significant struggle for control of Greece beyond Thermopylae, producing many other famous battles of similar or equal importance, such as the Battle of Salamis (480 B.C.), and the Battle of Plataea (479 B.C.). Salamis of which turned the tide of the entire war by sea, and Plataea, which dramatically concluded the war by land.

Book 20: The Advance

Xerxes and his forces marched southward for 3 days unhindered by any incoming forces after the fall of the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae. During the journey, Xerxes came across many groups of Arcadians, who had deserted/were let go by Leonidas’s forces prior to their final stand. When questioning what was transpiring in Sparta, the Arcadians revealed that the Carneian festival on August 20th was in procession, liking it to an Olympic festival of sport and prizes. Xerxes was perplexed that the Spartans celebrated while his massive army gained closer and closer to their nation. During their march, all of the fertile land of Phocis was demolished, as the towns and farms were burned to the ground for refusing to bow to the Persian empire. Despite the Athenians persistent calls for alliance, none of the surrounding Greeks in the Peloponnese agreed to make a stand with Athens in Boeotia and protect Attica, according to Plutarch. The Persian army decided to spare the Oracle of Delphi, who took a pro-Persian stance in their “prophecies”, only carrying off great treasuries from the shrine of Apollo.

Book 21: Into Attica

By August, the bulk of the Persian army had arrived at Attica, while the advanced guard had made it to the outskirts of the vacant Athens. Bradford notes that the Persian army’s senseless destruction of valuable crops of the lands passed over was an “act of stupidity”. Meanwhile, Themistocles and other Athenian leaders ensured that the inhabitants of Athens made a swift departure from their beloved homeland as the Persian army approached. Xerxes stood triumphantly as the first Persian monarch to occupy Athens, which was seen as the capital of the West and center of the rich lands occupying the Mediterranean. Xerxes now set his sight on capturing the fortified Acropolis in Athens, defended by stewards, treasurers and other poor men unable to fight in the battle of Salamis. Its value was merely symbolic to Xerxes and presumably could be starved out or bypassed without much difficulty. After the defenders of the Acropolis rebuffed the pro-Persian Athenian emissaries, Xerxes mounted an attack on the stronghold, which proved to be unsuccessful. Large boulders were rolled down the steep slope of the Acropolis onto the Persian invaders as a primitive style of warfare. But the fall of the defense was swift and sudden, not taking longer than a few days of struggle, following a secret unguarded side of the hill that was exploited under the guise of night by a scouting group. After the fall of the Acropolis all of its inhabitants were slaughtered, and Xerxes claimed the Acropolis and all of Athens as his own. In his triumphal exuberance, Xerxes ignored a wise warning from his brother Artabanus in Susa, “The end is not always to be seen in the beginning.” It is here that many in the Athenian navy argued with Themistocles over leaving their position in Salamis and the Isthmus line, who sought to preserve the unity of the fleet even in the midst of their occupied city. In replying to his dissenters, Themistocles channeled Churchill in stating, “But we still possess the greatest city in all Greece, our 200 ships of war, which are ready to defend you if you are still willing to be saved by them.”

Book 22: Sparring for Position

Eurybiades and his Peloponnesians realized that they had lost the debate against Themistocles, who persuaded the majority of Aegina (providing 30 triremes) and Megara (20 triremes) to remain at Salamis to continue fighting. In describing Themistocles’s ingenious strategy and inspirational motivation (as brilliantly depicted in the 2014 movie, 300 Rise of An Empire) to invest all attention into winning Salamis, Bradford states,

| “He himself had always known that Salamis was the key. Themistocles was not only a brilliant diplomat, wily politician, admirable strategist, but also a master-tactician. There have been few men like him in history.” |

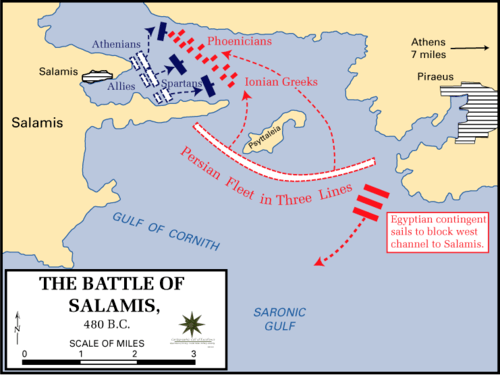

Themistocles’ plan was to fight the enemy in narrow channels to greater advantage their small numbers against the Persian fleet, who favored battle in open waters. Beating them at sea, Themistocles believed, would repel them to retreat in disorder and halt their progression on land. In persuading Eurybiades, Themistocles had with him a united front, something truly rare among allies, according to Herodotus. For Xerxes, relying on the naval intelligence of the Phoenicians was key, for they made clear that maintaining an adequate supply route to the army was impossible so long as the Greek fleet could strike out at them from Salamis; this island was the key to their whole campaign. Upon meeting with his naval commanders (most of them Phoenician), the lone voice opposing naval action at Salamis (deeming it to be a trap) was Queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus in Caria (birthplace of Herodotus). Her small contingent of five triremes proved to be the most capable vessels in Persia’s fleet behind the Sidonians in the battle of Artemisium. She advised that the fleet remain at the coastline and draw the Athenians out to sea where they will be dispersed and vulnerable to attack. Despite her passionate speech, Xerxes opted to follow the majority of his senior naval commanders to close in on the Salamis Channel. Xerxes however compromised in slightly following Artemisia’s advice by marching 30,000 troops to Megara to instill fear into the Greeks defending the Isthmus line.

Book 23: Eve of Battle

Xerxes’s noisy march of troops to Megara was intended to distract and divide the Greek fleet’s attention at Salamis. Themistocles brilliantly devised a plan to send a slave Sicinnus, to travel by boat under the guise of night to deliver a propaganda message to Xerxes and the Persian forces that the Greeks were fearful and planning to withdraw from Salamis. This, of course being cunning misinformation to throw the Persians off guard as to the fleet remaining at Salamis indefinitely.

Book 24: Seaborn Salamis

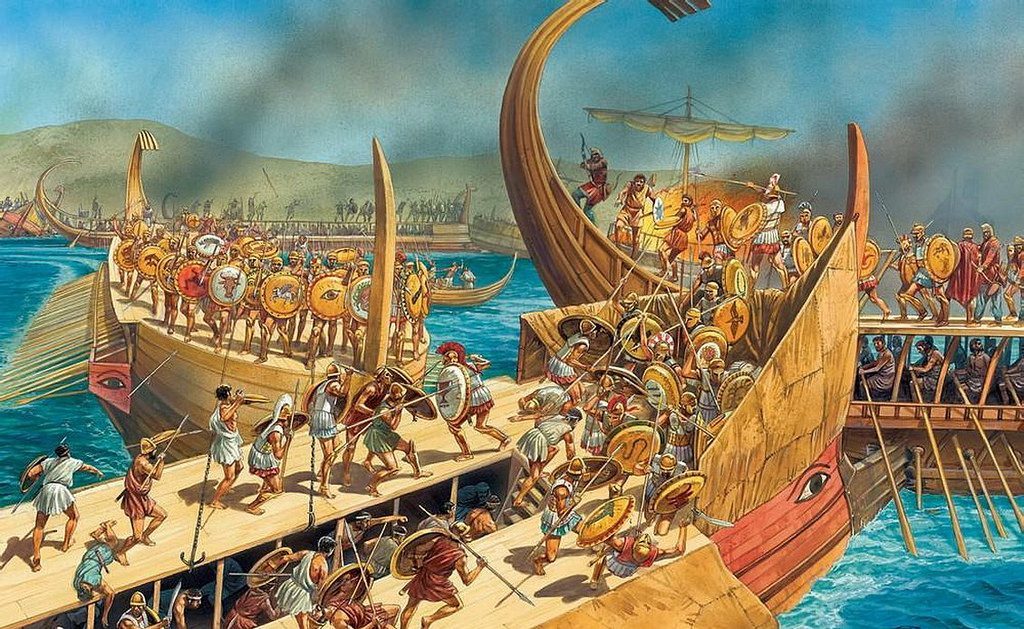

The heavily armored Egyptian fleet, which had proven itself capable at the battle of Artemisium was chosen for the task of blocking the narrow Greek escape route west at the Bay of Eleusis. As Themistocles (who had planned the battle of Salamis long before) coordinated with the allied fleet for a successful strategy, Xerxes made the gravest error in believing the Greek misinformation fed to him by diversifying his forces. He sent the Egyptians to block the Bay, while two squadrons were used to bait the Greeks around Psyttaleia, in addition to another group of 400 men sent to attack the island. The Athenians held the left flank, the Corinthians were stationed to the north, while the Peloponnesian contingents led by Eurybiades composed the right flank. While not entirely certain, according to Herodotus, the Corinthians seemed to have broken ranks and fled toward the Bay of Eleusis by the dawn of battle, only to fool the Persians into following them into the narrows of the Bay, and subsequently return to normal battle positions with sails hoisted. The Athenians and Peloponnesians circled behind the chasm of St. George’s Island and emerged in an orderly line, undetected by the Persians.

In addition to this advance from the north, the Megarians and Aeginetans lurking in Ambelakai Bay suddenly emerged and flanked the Persians from the sides, sending their ships into disarray because of their close ranks with little to no maneuverability in the narrows. “What the Persians had seen as a demoralized and fleeing enemy suddenly became a noose that tightened around their advance guard”, according to Bradford. The Athenian Ameinias of Pallene is credited for being on the forefront, using his trireme to clash head-on with the much larger flagship of the Phoenician admiral. Ameinias would kill the admiral and his first lieutenant during the ship boarding battle that ensued. Xerxes watched from a distance as his forces were humiliated in a chaotic ship jam in the straits of St. George’s Island. Each of the Persian ships were jammed together, and each incoming vessel was unaware as to the Athenian assault to the ship in front of them. Artemisia seemed to be one of the few commanders that maintained successful exploits for the Persian fleet during this time, prompting Xerxes to say, “My men have turned into women, my women into men!” Despite no longer having any plan or formation, the Persian fleet fought fairly well under the fear of Xerxes’s watchful eye. While the blame was primarily on the Ionian Greek contingents in Xerxes’s fleet, he was aware that they in-fact fought the greatest of his entire fleet. Xerxes had many Phoenicians beheaded for their unbearable defeat.

Book 25: Aftermath

The night following their victory at Salamis, the Greeks repaired their ships, expecting a return attack by the Persians. The naval historian Ephorus recounts that the Greeks lost around 40 triremes, while the Persians lost 200 (including those captured). The Persians had been completely fooled in battle, as the Greeks proved more superior in discipline and ability regarding battle tactics. Xerxes knew that his fleet was totally shattered and demoralized, and that the harshness of fall weather could break at any time following the current day of September 21st. The massive Hellespont used to enter Europe was now his Achilles heel which the Greeks could destroy at any time. The Persians were not a seafaring people and their defeat was faced by the many seafaring nations that composed of their fleet (Egyptians, Phoenicians, Ionians, etc.). While Themistocles supported sailing north to destroy the Hellespont, Eurybiades’s opinion to hold-back was accepted, as the dangerous gale-force storms of September would prove to be a threat to them (the same can be said for the fleeing Persians proving to be dangerous if they counter-attacked according to Spartan strategy). Xerxes continued his march north, leaving behind his chieftain Mardonius in charge of roughly 30,000 men.

Book 26-27: Winter; Spring

Briefly explores the difficult winter for both the Athenians, Spartans and Persian forces. Xerxes’s march further up north with his massive forces is liked to something of Napoleon’s disastrous retreat from Moscow, as Herodotus and Aeschylus describe many Persians freezing to death and drowning in frozen waters during the perilous ascent.

Book 28: The Road to Plataea

In the conflicts leading up to the final battle of Plataea, the Megarians ambushed Mardonius’s forces and killed Masistius in Boeotia, the second most important leader in Xerxes’s forces, dealing a tremendous blow to the Persian’s westward march. Spartan General Pausanias, leader of the Hellenic league, redeployed his forces westward to the deserted city of Plataea, favored for its flatlands and excellent water supply from the Asopus. The total number of allied Greek forces amounted to 38,000, mostly made up of Spartans, followed by Megarians, Corinthians and Athenians. Both sides refused to attack the other, remaining immovable for several days. Alexander of Macedon, although cooperative with Persia, often snuck over to warn the Greeks of Mardonius’s plans prior to the start of battle, eventually alerting one night that they would attack the Greeks by the next morning (which did occur). After a fierce day of battle, Pausanias met with his commanders and discussed the fact that there was only 1 days’ worth of food supply remaining and they could not hold their position for another day against the successful Persian calvary. Pausanias decides to move his forces further west while maintaining his supply route down the Dryoscephalae Pass.

Book 29: Decisive Round

Amid the march westward, the Persian calvary engaged the Greek forces and the battle shifted to a two-front struggle, with Pausanias and the Spartans facing the main weight of Mardonius’s forces on the rightwing, while the Athenians to the left faced the Thessalians and Boeotians. The Athenians and Megarians were hit hard by the Theban calvary, who cut down 600 troops to the left flank. Despite Mardonius’s persistent push on both flanks, not even his finest troops could overcome the battle-hardened Spartans, who were raised to master battle since childhood. Pausanias would gradually overwhelm Mardonius’s forces on the right-flank and Mardonius himself was killed by a distinguished Spartiate, Artimnestus who broke his skull with a stone. The left-flank, realizing all was lost, fled under the cover of Theban calvary. The morale of the Persian army had collapsed, leaving many to be slaughtered helplessly by the Greek forces. Bradford, in concluding the great battle, stated, “The battle of Plataea was over. The vast shadow of the ‘Great King’, king of kings, was lifted from Greece forever.”

Epilogue for Persia

Following Persia’s devastating defeat, Xerxes would pursue

his reign for the next 25 years, choosing to never invade Greece again. In 465

BC, Xerxes was assassinated by his brother, Hazarapat (“commander

of thousand”) Artabanus, the commander of the royal bodyguard and the

most significant official in all the Persian court. The assassination was carried

out with the aid of an eunuch, Aspamitres. Artabanus had served as Xerxes’s

adviser and while in Susa warned him “the end is not always to be seen in the

beginning”, after Xerxes proclaimed victory over the Acropolis in Athens.

Following the war, Artemisia was sent to watch over Xerxes’s illegitimate sons

in Ephesus. According to a legend,

quoted by Saint Photius the Great, some 13 centuries later, claims that

Artemisia fell in love with a man hailing from Abydos, named Dardanus, who

rejected and ignored her. In retaliation, Artemisia blinded him while he was

sleeping; ironically only amplifying her love for him in turn. In order to cure

Artemisia of the “passion of love”, an oracle advised her to jump from the top

of the rock of Leucas, but she was killed after she descended from the rock

and was ultimately buried near the spot. The legend remains that those who

leapt from this rock were said to be cured from the passion of love.

Modern Day Conclusion: Victory for ancient Greece = Victory for America

Without a doubt, the many victories of the allied Greek nations over the span of the Greco-Persian Wars (492-449) represented an unprecedented and miraculous triumph over Persia, the greatest imperial power of its time. Although the final stand of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans (including 1,700 other brave Greek soldiers) was overwhelmed by the tidal wave of over 150,000 Persians thus this unparalleled display of bravery in the face of insurmountable odds would forever inspire future generations of Greeks to protect the freedoms of one’s country. Even in 2019, Greece celebrated the remarkable 2,500-year anniversary of the infamous battles of Thermopylae and battle of Salamis, honoring key sites, notable figures like Leonidas, issuing commemorative coins, and hosting Hollywood star Gerard Butler (who played Leonidas in the iconic movie 300). “These two decisive battles are seen by many to mark the very beginnings of Western civilization itself, as united forces of Greeks won over the Persian threat, paving the way for Greek classical antiquity to flourish,” according to an article. This profound sacrifice of men at arms giving their all to defend Thermopylae would greatly inspire the renowned victory of the Spartans at the Battle of Plataea, where they fought with greater ferocity and skill than any other Greek nation present.

In continuing my Part I comparisons to the modern day Thermopylae of politics, regarding the spirited defense of President Donald Trump’s innocence amid his intensely politicized impeachment trial, Leonidas and his fearless 300 Spartiates represent first wave of defense against the impeachment onslaught: the most conservative House Republicans (many members of the House Freedom Caucus). Despite the greatest efforts by Representatives like Jim Jordan (R-OH), Matt Gaetz (R-FL), Doug Collins (R-GA) to explain the facts of the July 2019 phone call transcript between President Trump and Ukrainian President Zelensky, House Democrats comprising the majority, passed the two articles of impeachment—”obstruction of Congress” and “abuse of power”; an overwhelming push, despite the facts of the case, as representative to how the Persian ground troops and Immortals overwhelmed Leonidas and his men to meet Xerxes’s unquestionable demands, despite the devastating casualties they faced. Both House Republicans and the Spartans gave their all to produce a marvelous defense that was nearly impenetrable, if not for the majoritarian advantage of House Democrats and the Persian attackers.

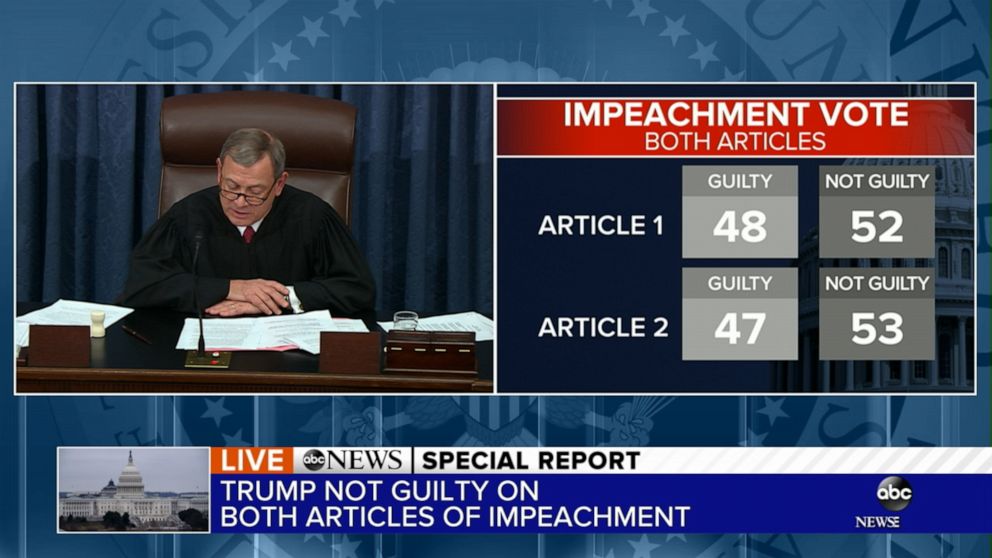

The second phase of the impeachment trial in the Senate represents the second major phase of the Greco-Persian Wars, namely the battles of Salamis and Plataea, where the allied Greeks ultimately claim supreme victory. President Trump’s legal defense team, comprised of outstanding lawyers like Jay Sekulow, Pam Bondi, Alan Dershowitz, and Pat Cipollone, personified the cunning and brilliance of the Athenian forces at Salamis in completely rebutting and dismantling the Democrats’ proposed articles and arguments, just as the Athenians completely outmaneuvered the entire Persian fleet despite their skillful naval prowess and careful planning by the Egyptians and Phoenicians present. The final vote on the two articles of impeachment where every Senate Republican (with the exception of Mitt Romney’s traitorous betrayal, reminiscent of the cowardly Ephialtes) represents the unwavering unified alliance by the Greek nations at the Battle of Plataea with Pausanias leading their side to victory against Mardonius’s Persian forces, just as Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell maintained Republican unity among a diversified group (even among moderates Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski) in a vote to acquit President Trump, repelling every argument contrary to the facts of the call transcript made by Minority leader Schumer to convict Trump. As author Ernle Bradford described the Spartans’ impressive might and superiority in battle over the massive Persian onslaught at Thermopylae (and later at Plataea), “the outcome was inevitable”, in deciding President Trump’s unequivocal innocence in what was arguably the most partisan and unconventional impeachment trial of American history.

*N.B: This essay is based in part on Ernle Bradford’s book, Thermopylae: The Battle for the West, republished by De Capo Press in 1980, and, Great Books of the Western World, Vol. 6: Herodotus – Thucydides, edited by Robert Maynard Hutchins (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952), On Fate, examining the works by Herodotus and Thucydides; Ellis Washington, The Progressive Revolution, Vol. 5 (2017), pp. 153-56.

Category: Socrates Corner