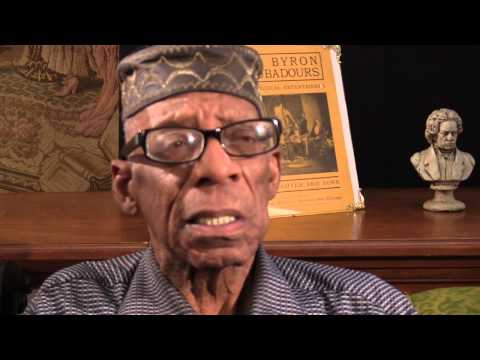

Prof. Arthur LaBrew, Musicologist

A Biography Of Prof. Arthur Labrew

—————————————————————————————————————

(Excerpts from)

International Dictionary of Music & Musicians

4 volumes (2013)

By Professor Arthur R. LaBrew

Book ordering info:

Arthur R. LaBrew Michigan Music Research Center, Inc. .

220 Bagley St., Suite 840 Detroit, Michigan 48226

Email: DetroitMusic1865@yahoo.com

Office: 1-586-804-6895 Hard Copy Cost—$80.00 (per volume) plus $10.00 Postage/handling)

PDF electronic copy—$40.00 (per volume)

—————————————————————————————————–

Excerpts From the Book

Musicians of Color

and family relationships

found in

Various Sources

Antiquity

to the end of the

Nineteenth Century

Arthur R. LaBrew

1969-2010

——————————————————————

© 2010 Arthur R. LaBrew Michigan Music Research Center, Inc.

220 Bagley Street Suite 840 Detroit, Michigan 48226

Arthur R. LaBrew, Editor-in-chief

Ellis Washington, managing/associate editor

Thornton Hagert, consultant

Michael Montgomery, consultant

————————————————————————-

THESE VOLUMES ARE DEDICATED

TO THE MEMORY OF THOUSANDS OF

MUSICIANS OF COLOR WHOSE CAREERS WERE OMITTED FROM GENERAL HISTORICAL BOOKS.

MAY THESE FEW LINES GIVE THEM

A FOOTPRINT IN THE SANDS OF TIME!

————————————————————————

INTERNATIONAL DICTIONARY

OF

MUSICIANS OF COLOR

A source book reflecting more than cursory information about musicians of color (black or posing as white) has been a worthy goal for serious music scholars. As an ethnic group, “musicians of color” (i. e., boasting African lineage) deserve to have their history written separately just as other ethnic societies have done. Neither the 18th through 20th centuries had supplied a comprehensive document embracing the entire period – antiquity to 1900 – although numerous material has been available but unassembled.[1]

Whence Such Curiosity?

As early as 1948 curiosity about black musicians engaged our attention. The annual meeting of the National Association of Negro Musicians, Inc. at Columbus, Ohio brought us in touch with a large cadre of musicians who had developed careers beginning before the turn of the century. Information about their careers was seemingly non-existent.

While attending the Oberlin Conservatory (1948-1952) we were in touch with blacks studying music in an academic manner. However, the question “What will they do with their new skills in the future” did not enter our conscious thought due to selfish interest in our own career.

It was not until we began study in New York, the mecca for black enterprise, that we began to see and hear hundreds of musicians who, like myself, were forging careers. In attending their performances in churches, Town and Carnegie Hall and in private sessions it was realized that I, too, would become a part of this musical aggregation.

Slowly but surely, we were introduced to vocalists, instrumentalists, writers and the like, who in previous decades had made impressionable contributions designed to elevate the musical advancement of the race. Alas, such contributions were hardly noticed in music encyclopedias and dictionaries written to expose new contributors. Our own study in musicology was a typical subject by our teacher, Gustave Reese – the Renaissance period which, then, heralded no knowledge of black musicians. That was what was required for our thesis.

Reese, however, was an adjunct teacher at the Manhattan School of Music and he taught four of us in his home – a treasure trove for historical research. At one session, we elicited the comment that the black music history was an area which had escaped the scrutiny of scholars both in Europe and America and worthy of a greater pursuit.

In paying homage to Reese, we began to accumulate information from many musicians who opened our eyes to when, where and what were their particular contributions. Our concern was “Who else was left out?” For those who were deceased “Did their relatives have additional materials, published and unpublished?” Fortunately those questions produced positive results and became part and parcel of our personal interest.

Therefore we continued to develop this interest and compiled files reflecting the contributions of these musicians but it was necessary to establish a foundation upon which to build a solid base.

Red flags had appeared for many years. Einstein had noted madrigals which used supposed “negro” dialect.[2] Paul Nettl had written “Traces of the Negroid in the ‘Mauresque’ of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries”[3] However, a large amount of music called negro, negriya, gallego, guineo, congo, calenda, etc, began to appear in renaissance and baroque sources of Spanish speaking countries.

Another study titled “The First Appearance of the Negroes in History” by Dr. Hermann Junker[4] provided another part of our initial thrust. He explained that the necessity of throwing some light on the history of Blacks [N. B. the capitalization of the word] from the Egyptological side needed no justification because Egypt was a part of Africa and had the oldest history accessible (at that time). Relying primarily on excavated materials his attempt was admirable.

What he learned was that evidence of Blacks was frequently discovered among the many excavated artifacts in different regions. At page 128, fn.2 he quotes from Wreszinski’s Atlas zur altaegyptischen Kulturgeschichte, Pl. 23, of the lower line of soldiers: “On the right are marching seven Negroes, the first two of which are carrying trumpets (?), while the five others are armed with throwing-sticks” to which Junker disagreed and urged comparison with real contemporary representations in the tomb of Sebekhotpe, ‘Abd el-Kurneh 64, Pl. 56 in the Wreszinski report. Thus these two sources, if proven to be true, would fall in our section of Anonymous participants.

His report ended with: “The great victories of the New Kingdom brought Egypt, at about 1500 B.C., for the first time in direct contact with the Blacks, whose habitat is to be sought south of the Fourth Cataract. At the same time we meet them on the coast of Somâliland, at about the same latitude. The territory of the Negroes proper thus extended at that time almost exactly as far as at present, or only a little further northward.”

Other sources such as in paintings and the like bolstered the claim that Blacks were known in many civilizations. Indeed, UNESCO’s World Art Series published by the New York Graphic Society (1964) and others gave many representations of the Black presence in different societies of the world.

Admittedly the red flags deserved some type of music critique and especially those items reflective of the presence of black people in musical situations.

However, our primary interest was in music representations of Blacks which during our history studies at Oberlin and the Manhattan School of Music failed of pertinent mention.

As early as 1912 the following suggested a partial rationale for this historical dilemma of omission:[5]

In assigning places in history to athletes, actors and musical performers, we must not mistake transient popularity for permanent fame. An athlete, actor and musical virtuoso is only applauded while he is in the limelight; when he retires he is soon forgotten and interest centers in a new star. . . That is the fate of a musical entertainer . . . I do not know whether getting applause as an entertainer is in reality breaking down race prejudice and crossing the color line . . . Even in slavery days the darkey who could play monkey, who could sing and dance or pick the banjo and play the fiddle, was popular with his master. While musical and artistic performers do break down the barrier between the races, we cannot exactly call them–picturesque and entertaining as they are–great figures in history, dynamic forces in human progress.

Although pertaining to other fields of endeavor this partial truism has been sanctioned throughout the history of mankind with certain prominent figures heralded as “geniuses” of the highest rank – but then genius can only be defined in relationship to mediocrity. This observation should certainly occupy the thought of today’s musicians desirous of entering this field that there are always choices to be made regarding that which is transient against that which will become permanent.

Still further were the remarks of Harry Lawrence Freeman, who began summing up the achievements of musicians and himself a writer of Broadway shows and opera. He was expressly concerned about the “higher altitudes.”

The Negro in the Higher Altitudes of Music in this country and throughout the world.

STATUS

The Negro occupies a unique position in the realms of musical art. I employ the term “unique” rather than” important” inasmuch as he has not as yet revealed to the world at large his true musical value. While the divine gifts of native talent, inherent taste and a certain adaptability in musical parlance have finally been conceded unto the Negro, his capacity for artistic achievement and logical development is still a matter of doubt and uncertainty. [Ed. italic.]

PROSPECTIVE

Yet as babbling brooks, murmuring streams, roaring torrents and tumultuous cascades, each plastic and concrete in its own diminutive and individual form, are bone and tissue (metaphorically) of each and every great and noble river, and the latter in turn offering fealty and allegiance unalterable to the vast and mighty seas and oceans, then also is the Negro’s capacity for the highest musical achievement fully assured, inasmuch as he has succeeded to the fullest extent in meeting the demands of the past decade for such smaller art forms in vogue through the only universal means of exposition at hand–the legitimate Negro theatrical and musical comedy organizations.

NATIVITY

It remained, therefore, for our own blood-brother, the recently lamented Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, of London, England, to bequeath, among other excellent works, a series of compositions for piano-forte.

These works, endowed with masterly treatment, are based upon the sorrow songs of our own Southland. Though diminutive in form, they are eloquent in suggestiveness and promise of what the future holds along the lines of symphonic and operatic development. Among other works that Mr. Coleridge-Taylor has bequeathed to posterity and the world at large, is the famous “Hiawatha” trilogy, an Indian cantata in three parts. The “Blind Girl,” “The Atonement” and “Endymion,” also in cantata form, followed, interspersed by numerous smaller compositions for violin, voice, piano-forte and grand orchestra.

Under this head might also be included certain successful song forms and ensembles as well as obligato choruses. Probably the first original works of larger mold and with a decided tendency toward the classic or operatic appeared in the late Ernest Hogan “Rufus Rastus” musical comedy company–seasons 1906-1908 inclusive. As the following works are original products of the writer of this article, they are enshrined herein merely as a matter of musical sequence.

In 1936 Maud Cuney-Hare (1874-1936) attempted to tackle the difficult periods with proven documentation and she, like her predecessors, wisely limited herself to known published materials or to information which she had personally witnessed. Co-incidentally, both Hare and Trotter (1844-1892), independent researchers, were without the ultimate in “scholastic” credentials[6] while Edward D. Seeber added various opinions about French literature mentioning blacks during the second half of the eighteenth century.[7]

The 20th century has been most productive in attempting to historically research the lives of musicians of color of previous generations as well as introducing newer participants “for consideration.” In countries outside the United States, non ethnic scholars have often carried on the task of identifying source material for the study of musicians of color. Then, too, within the confines of the United States, some non ethnic scholars have often left an indelible impact upon many aspects of scholarship pertaining to musicians of color and their contributions are recognized.

However, some writings emitted a tasteless scent and often viewed the contributions from this ethnic class of musicians through rose colored glasses. As witnessed in the histories of European countries, the contributions of their musicians are terraced and only those at the apex are given consideration as their greatest music contributors. Thus students of general music history were not alerted to a plectra of ancillary musicians and materials omitted solely because researchers of the first rank have been unable to bear the expense of so great a project.[8]

Such failings have been detailed in our many writings on musicians of color which refute the impression that only composers or performers of the “first rank” should carry the weight for an entire ethnic group. This fact is easily confirmed by looking through any library catalog for such subjects as black music teachers, music critics, music entrepreneurs, music inventors, etc. Within the true African music ethic all musicians are viewed as contributors of materials whether original or arranged.[9] Admittedly, almost no single published source book has permitted a look at this complex picture and thus the value of “lesser lights” has been severely discredited.

When recognized academia insinuates that lesser acknowledged contributors and their contributions are but “shadows” in moments in history it tacitly asseverates that their existence is without merit. Thus academia’s failure translates into “dissing” those most responsible for shouldering the careers of promising artists. [10]

“Divide in order to conquer” may have been a convenient method to record historical moments but, in reality, when re-assembled and glued to a common frame is often Frankenstein-like in its finality.

In this volume, an attempt has been made to furnish the reader with as many leads as possible for future research. With new writings being assembled and published in greater quantity than in previous years, our understanding of the supportive role played by musicians of color throughout the world should be brought into sharper focus.

We are pleased that we can now offer a tool to some students of music history. In developing this document, our efforts were not guided by previous models therefore new concepts had to be formulated before they could be implemented. For example, in noting black musicians in the American armed forces, it was thought more prudent to list them together rather than as individual entries unless there was additional information, which necessitated a separate entry. Our effort has not yet been superceded!

Black contributors throughout world history is an important subject but alas, the radar screen was raised and their names and careers seemingly vanished! The Renaissance aristocracy set the pace and employed blacks as servants. They allowed painting that often showed a young black servicing them but there ends their life story. They simply disappeared!

In refusing to recognize the “simply disappeared theory” it was hoped that future examination of existing records of these “aristocratic dynasties” might give additional reference especially to any possible black communities in which these transposed blacks might have lived and how did their musical sensibilities relate not only to their particular group but to the entire music community. Some answers have been revealed but still lacking is the subject of their contributions to the arts. Therefore it is hoped that more and more pertinent details will be revealed in the future.

Today, we are receiving information via the reasoning of griots – story telling, i. e., fiction based on fact often stretched for a specific purpose. But events preparatory to the existence of such facts are seemingly lost. For example, the song “Home, Sweet Home” may seem like just another ditty, today but at the time of its creation when many were displaced by slavery, indenture or even immigration, the mention of “Home” brought tears to its listeners (viz. movie “E T”).

In modern society, sentimentality is not always cherished as in previous years. Therefore the suppression of one of the most fundamental emotions has produced a partially disturbed society.

Our presentation attempts to rescue as many segments about music presenters of color. Whether or not one agrees with this approach is their problem not that of the author. The validity of the information sterilizes their ignorance!

Then, too, we are writing from a professional-historical perspective not as an outsider attempting to delve into what is often a personal and rather restricted subject area.

What we have witnessed in early writings (both African and Afro- societies) was the tendency to describe the action of large groups either in ceremonial events or at times of merriment but very little about the individual performers. This procedure continues in modern ethomusicological studies and one must remember that in time of merriment both normal and abnormal manifestations of music, poetry and dance cannot be considered as part and parcel of black people collectively. Such collective actions have varied over the centuries and often designed to titillate rather appeal to specific ethnic traits. Early African manifestations have been labeled primitive but as their civilizations advanced many were accordingly altered. To characterize primitiveness as a special ‘African only’ root shows great ignorance by failing to note that Blacks born outside the mother country may have a different ethnic view of their position within the local atmosphere. Evidence supports the general thesis that customs involving human nature are common to all races of man and do not representative ethnic purity.

Primary sources appear throughout this presentation. Writers who have (or will) use these discoveries without proper acknowledgement may be deemed . . . (unprintable).

Our presentation respects the ethnological approach but rejects any premise that seeks to group all of its participants under one umbrella. Nor does this work pretends to be a history. “Histories,” in general, must omit materials of possible greater consequence. Their conclusions are often just opinions which can and are often challenged. Opinion is not fact!

Some white writers were critical of our efforts! One suggested that in our list of run-away colonial musicians that we pick one and write a biography. The faulty logic presumed there was additional information (incorrect) and tie up my time seeking a needle-in-a-haystack.

Still another suggested that our writing suffered because we did not fully explain extraneous details surrounding each event in which blacks were highly visible thereby forcing the non-historical reader to look elsewhere for any possible connective tissue. Again this method was not our concern unless such tissue was readily apparent. There are no “what ifs” or “is it possible that” in our writings.

In our musical training our first professor did not pretend to write a history (Reese, Music in the Middle Ages or Music in the Renaissance). Subsequent scholars with whom we worked were likewise careful in presupposing that their writings would carelessly be labeled a “history.” Their judgement was very wise.

Since we first began our serious study new technological advances have been invented and often passes information without attribution to the writer first [N. B.] who used his own original sources to make his presentation. These writers then suffer a great monetary loss as well as a loss of prestige. We are not sympathetic to information taken from such media!

With many writers in mind one is aware that some scholars work through an intermediary in publishing their findings. One despairs when the intermediary continuously writes “according to!” The “according to” writer has often read another source (generally unmentioned in his text) thus covering up his adversary’s sources. This is what one would call “usury” which has plagued so much in writings about the Afro-American music legacies!

As a musical people we have failed to completely substantiate our own musical histories. Others have tried to cover materials related to the subject but many worthwhile projects have never come to fruition.

As a one-person endeavor we are mindful of recriminations that surfaced at the time of Eileen Southern’s Music of Black Americans and hope others will recognize our merits and deficiencies and add useful information in works of their own. Recognized deficiencies are noted but with an eye on supplying corrective tissue.

The Procedure

Biography is often a difficult area in which to pursue exact research. Some writers prefer a method that relates to the “what has he/she done concept that has been recorded either in print or some other means” thus admitting musicians most often mentioned in published notices but, in reality, played a lesser part in the total scheme of things. This method also produced skeleton-like outlines of the personality and which summaries fail to give qualitative substance – therein lies an even greater tragedy.

Thus little of the inner personality of the musician is unrecorded and readers are often confused in their judgments of their particular worth. We, too, cannot issue judgements of the many musicians mentioned in these volumes, however, future researchers will be aided by carefully exploring the era in which the musician lived, his triumphs, failures and adversarial efforts in music making.

Our first approach utilized the ten-year American censuses which were first randomly perused by cities for “black/mulatto/Negro” persons identifiable as “musicians” with some African heritage. After gathering that data a recheck of earlier censuses was made to confirm the veracity of the former and to secure other genealogical data.

In the matter of those known to be musicians, but not designated as such in the censuses, it was necessary to do a third check to see if birth and other data could be paired. This was especially necessary when the designation “musician” was only found in a particular source.

Lastly, information retrieved from pre-existing biographical materials (such as newspaper accounts) needed to be rechecked. The enormous amount of time needed to do this search prevents this publication from being complete and, hopefully, will be continued by future researchers sifting through other kinds of data ranging from court, criminal, land, tax, voting, birth, christening and death records, etc.

In this initial effort, musicians who acted in consort are entered without the follow up of detailed biographical data. This was especially noted where bands and orchestral personnel were reported in various regions but the necessary time to research each participant could not be easily undertaken. Therefore they are usually grouped together.

Censuses for some countries have been difficult to secure. In the Latin countries such places as Cuba need better exploration during the 19th century. Contrastingly, materials in the 1910 census of Puerto Rico marked “N” [=negro, black] or mulatto are used since the 1920 census was altered for political purposes. We retain the listings in the 1910 census.

In America, the earliest records, birth and baptism dates of black musicians through church records were not easily available. Then, too, other pertinent sources have not preserved the necessary documents for a complete record. Secondary sources have been used but only as a point of reference. In instances where musicians deliberately changed their names the process became difficult. During the enslavement period, run-away slaves changed their names for obvious reasons. One need not be surprised if the same holds true in many present day instances.

Some early notices provided information which black travelers brought from experiences in different countries or their satellites. This led to our inclusion of blacks from other areas in the world from which another perspective could be included. Blacks who traveled (especially as sailors or indented servants) surely brought back some of their experiences. Although a minute amount of such literature has been retrieved, the oral tradition presupposes that this was one of the means by which blacks became aware of black music identities in other cultures.

The amount of information secured in this volume is miniscule – a fragment of a subject that should be more rigorously investigated.

The future of black music research depends upon many diverse factors including the creation of a cadre of scholars committed to rediscovering and utilizing untapped sources. More important, however, will be their rediscovery and exposition of musical concerns within the framework of the period in which the musician lived–with and without its flaws. Information without irrefutable documentation should be avoided!

In this presentation original prepared biographies are not “reinvented” or regurgitated. However, admitting new and particular aspects of a musician’s career does add additional coloration to an existing biography but does not, in itself, invalidate the initial source.

Conclusions:

The first object was to secure a definition, which applies to “black music.” The simplistic definition used by some – “all music written or performed by black composers” – fails to take into consideration where the musician was born and the influence his environment imposed on his creativity. Color may identify the person but certainly does not define his music, style or his contributions.

By analyzing styles, one might arrive at a better definition of the musician’s involvement which may include ethnic, non-ethnic, original and burlesqued efforts.

1. Ethnic pertains to music prepared for the consumption of the masses employing

ethnic artifices.

2. Non-ethnic defines music prepared the consumption of an “elite” society and

generally employs artifices more nationalistic in character.

3. Original music is that prepared for personal consumption with or without regard

for ethnic or non-ethnic styles.

4. Burlesque is music prepared in imitation of any of the above.

Each category has its own adherents, both black and white. However, ethnic style (which can be easily be burlesqued, item 4) has apparently received more treatment than items 2/3.[11]

The materials in this study should dispel forever the generalization that all blacks enjoy and perform the same kinds of music – or that all blacks are able to sing or perform music – or that all black composers should write in only black music styles. There are no borders in defining materials which black musicians have used in developing their art.

Lastly, those writers who deliberately “write out” [“proscribe” in nineteenth century terminology] musicians who elect not to use boundaries prescribed by the so-called “keepers of the keys” do an immense disservice to recognized scholars.[12] Music evolution stands on its own merit!

In this Dictionary, most references to “musicians of color” of New Orleans have been detailed in our Afro-American Music Review Vol. 1 No. 2 (1984), New Orleans Before Storyville (2000) and further developed in Afro-American Music Review 5, No. 2 (January-June) 1994 reviewed in Inter-American Music Review XIV No. 2.

In making our information available (our cataloging was begun during a tenure at the District of Columbia Teachers College, 1969-1971) we were especially aided with materials from the Zelma Watson George catalog at Howard University.[13] The lists of most works were searched at the Library of Congress as time would permit. Titles of other projected works were taken from cover sheets and on the music itself. Therefore many items appear without a publication date (see especially under Justin Holland). Likewise, the copyright number has often been omitted to save publication space.

Then, too, the majority of works were found only by personally examining the copyrights not in the general collection of the Music Division of the Library of Congress but located at the copyright repository at Suitland, Maryland. This was an extremely tedious and slow process in the earlier years. Fortunately, the Music Division filmed much of this material dating from 1870 to 1890 and a catalog prepared for quick references. As far as we know, these catalogs are available for purchase.[14]

Music scholars certainly have much homework to do in music cataloging and disseminating this information than has been possible in earlier years.[15]

This Dictionary of historic black musicians does not interpret the music and seeks little aesthetic pronouncements. It is strictly confined to original source materials or, in instances where extensive biographical writings exist to minimally extract pertinent historical data.

Where interpretive material already exists by or about musicians, it has not been generally noted or listed.[16] Secondary interpretations by others may or may not be mentioned unless they are in severe disagreement with verified factual data.

We have used the musicological [N. B.] approach to unmask the history behind the history of musicians of color and their musics. Summaries or completely new articles were re-written or re-worded when additional materials rendered the old versions completely obsolete (á la Grove, 1909 et alia). Thus some biographies occupy more than normal space in our work.

Biographies of pre-eminent Afro-American musicians are usually not given much space unless corrective or supplementary tissue is supplied. Such material is generally available in most libraries.

Oft times even the black press could be fooled. For example, the Colored Opera Troupe of Mr. Albain which flourished during the 1850s in London (picture of the troupe given in Arthur R. LaBrew, Afro-American Music Review 1/1 (1981), p. 187) fooled the Cleveland Gazette of March 19, 1887 who mistakenly thinking they were real black men published the following: “A colored opera troupe appeared at the Oxford Street Gallery, England, in 1858.The names of the performers were Messrs. Willis, Kelly, Albain, Gance, Morrill, Wells, Montgomery and Barrett. They played a weeks’ engagement to large and appreciative audiences.” Rechecking such sources were necessary before attemting to enter them as real blacks. Many writers have often been careless when reprinting unproved information!

Summaries of events in a musician’s life usually found in encyclopedic works or extended articles often neglect the particulars of research and are unusable because of their restrictiveness.[17] Far too many writings fail to identify materials already “discovered” because of their limited investigative abilities. Thus the identities of its real discoverers are buried until some competent scholar exposes this inequity.

Today, we are witnessing many new publications attempting to expose various elements of the black culture. Among these attempts, “Spirituals” are now given the “bow-tie” and formal dress treatment thus losing much of the soul-searching emotional feel. To the older generations such exposure is unwelcomed, however, some new writers appear not to have a full grasp of situations and esthetic overviews of previous generations of black culture. Writers in this troublesome field of research should be aware that the logic of new generations does not supercede the logic of previous ones and persons having additional information may easily refute inaccurate conclusions.

Among other such citings are many new hymnals using melodies and texts arrangements of many older songs. Often, complete verses are omitted, the music is modified, the text is changed (from the original) and unwelcomed orchestra-like accompaniments of electronic equipment serve as excessive baggage in places where simplicity would be more appropriate! Sophistry is not always a sign of genius!

Hymns, as a part of the music liturgy, are generally used in congregational settings. Complex hymn writing obliterates both its purpose and narrative. Ornate hymn writing is best left for the more highly trained choral groups.[18] Unadorned hymns often challenge the singer/singers.

In determining which countries to include in this volume, we have let ourselves roam freely and when such information was at hand it was introduced. Unfortunately every country where blacks resided and made musical contributions is yet beyond our scope, viz. Paraguay.[19]

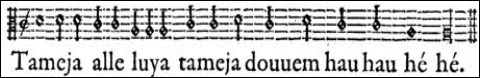

The last and important question involves new discoveries of America’s past. Should we be adding more substantive information or rely only on what we have already assumed? If additions may be welcomed then the following item was recently rediscovered of American Indians and is reported since it gives scope to some of the tonal attributes of that period and to which were often exposed. We could find no mention of this example in any current American writing.[20]

It is found in L’Histoire du Nouveau Monde ou Description Des Indes Occidentales (Iean De Laet, d’Aneurs.) Pub. A. Leyde, Chez Bonaventure & Abraham Elseuirs, Imprimes ordinaires de l’université ÌIÉ IÉÌ xl and reads”

Ils ne sont du tout ignorans des ars mechaniques, cas ils taillent en bosse des images á la grosse mode, non pas pourtant les honorer comme idoles. Ils recreent leurs banquets ou festes qu’ils noniment Tabagia, de certaines chansons aussi bien que les autres Sauuages, & au ton d’icelles ils donnent d pié conre terre, ou bien ils salutent; leurs Magiciens s’en serunt aussi. Lescarbot François en a exprimé quelquesumes en musique, l’une desquelles nous adiousterous ici.

Le chanson achenee, tout les autres sespondent He é é é. C’est chose esmerueillable d’où leur est venu ce mot Alleluya, leques Lescarbot asseure avoir plusieurs fois parfaitement ouy prononcer, ie m’en rapporte à c qui en est. Voila ce que nous auions à dire des Sauuages, maintenant nous poursuivrons le reste de la Continente.

Such telling evidence easily demonstrates the necessity of continuing research among the new arrivals in early America.

In using source materials we have tried to give the reader information that contains additional bibliographical entries that may be unknown or unavailable to them.

All of our entries are but recitatives – the arias must still be written until the entire “opera” is completed!

In summation we have tried to dispel stereotypes of previous generations. Attempts to lock in their contributions to certain genres invokes Shakespere’s immortal words “To be or not to be.” For example, we may have heard “low-down” blues during our musical time frame but does not mean that they were part-and-parcel of our musical interests.

Foremost in our writings are the listing of sources (quellen) which first present historical evidence. In assigning birth years spurious dates are sometimes mentioned. This procedure is often lacking in far too many modern expositions masquerading “in so-and-so’s work” and vaunts itself as under the egregious theory of “look what I have discovered” as if it were the “first.” Such outrageous acts have prevented rightful researchers of new materials from assuming their well-deserved place among others of similar standing.

Today’s students should be aware of a cadre of researchers who disdain presentations that omit the names of important contributors whether Black or White or invisible!

The Different Cultures

The subject matter of “musicians of color” has not been an easy task to assemble. Indeed, the history of people of color in general literature has often been defined only in relationship to the events within the dominant culture. The sagacious scholar should be able to pinpoint the various periods in which such music participants lived and worked within those current venues. For example, the writings of antiquity provide glimpses of musicians of color as they relate to that society. These individual expressions cannot be made to appear as a legitimate experience of the entire society from which that black person was apprehended. Antiquity has provided us only with a general outlook concerning black musical styles and very little of the individual life style or even their names (see Anonymous).

Likewise, the period from the 10th to 15th centuries appears to be a better starting point for learning of the music experience of blacks although often perceived with cultural biases. During this disporadic period, blacks were transported from their native surroundings and forced to accept new identities within the society. Where this has occurred, the observations by writers, and more important by watchful musicians, have resulted in some notable discoveries. Nowhere is this more conspicuous than in the Italian, Spanish and Portuguese countries[21] and their satellites which have identified such African type genres [=black] as villancico, negros, moriscos and other such nomenclature.[22]

Italy has discerned the music practices of its blacks and its composers have written of their onomatopoeic uttering. What is more important, however, is that some compositions give some indication of their rhythmic and rhyming techniques. There are many such extant examples in madrigal literature but there has not been a separate study of that genre. [23]

Portugal has provided us with at least one early important musician of color, Vicente Lusitano [see further in text] who was active during the period of the 1500s. His activities were also witnessed in Italy and possibly Germany.

However, this is still a difficult period because notices of music of or by blacks in many lesser regions have been unfulfilled. One example is in China which imported blacks during the 7th to 15th century [see Item Anonymous 618-907 A. D.]. Another is in Germany (see Anonymous 1800s) but recent information has augmented our knowledge of drummers and musicians from that country (see Gustav Albrecht Sabac el Cher, 1868-1934 and Elo Wilhelm Sambo aka Josef Mambo, b. 1885-1933). Again no separate study enhances any tradition.[24]

On the other hand, the importation of blacks to the Latin American countries has provided one of the best examples in exposing the music of both the slave and free black musicians, especially Brazil whose ties with Portugal are often highlighted in many publications.[25]

Another of the leading experts, Francisco Curt Lange devoted his time and expertise in tracing a myriad of eighteenth-century black musicians of Ouro Prêto Brazil.[26] Their music rarely contains easily visible ethnic traits. The slave population of the Municipality of Vila Rica to 1823 taken from Donald Ramos was: [27]

| Year | Population | Year | Population |

| 1718 | 7,110 | 1745 | 20,036 |

| 1720 | 10,965 | 1749 | 18,293 |

| 1722 | 11,859 | 1815 | 5,937 |

| 1724 | 13,757 | 1818 | 5,968 |

| 1735 | 20,863 | 1823 | 5,391 |

| 1740 | 21,165 |

The slave origins have been identified as follows in 1738 (total 7524):

Brazil Mulatto, Creolo Black, Indio/Caboclo

Portugal – Africa

Bantu-West Coast, Benguela, Angola, Congo, Mongolha, Gongella,

Cassange, Camba, Sabara, Timba, Gold coast,[28] Mina, Nago, Fam,

Courana

East Africas Mozambique

Other African countries

Ladaro, Lada, São Tomé, Cobrana, Rebola, Cabunda, Cabo Verde

Other African countries India

However, lacking is substantive information about the slave music practices. Although Ramos does identify the batuques (1726 and again in 1754) but in general little else has been identified.[29]

Ramos also notes the origins of the Lay Brotherhoods of Vila Rica:

Brotherhood to 1726 Date Parish Membership

N. S. do Rosário 1719 Antônio Dias Black[30]

N. S. da Conceição 1712 Pilar Mulatto

N. S. do Rosário 1715 Pilar Black

1726-1752

N. S. da Boa Morte 1736 Antônio Dias Mulattoes

N. S. da Terço 1736 Antônio Dias Integrated

N. S. da Mercês e Perdões 1743 Antônio Dias Black[31]

N. S. das Mercês 1740 Pilar Black (Creole)

1752-1822

Arciconfraria do Cordão 1760 Pilar Mulatto

São Francisco de Paulo 1780 Pilar Mulatto

Santa Cecilia 1816 Pilar Musicians

(Mulatto)

The brotherhoods were eventually responsible for the phenomenal growth of music under the aegis of the Catholic Church. Nonetheless the relationship between the slave and free black in the acculturation process of Vila Rica and other Brazilian satellites still needs to be more sharply defined.

Lange’s exposition of the musical activities of the “free” blacks has been masterful but much remains regarding that part of the population that was more ethnically oriented.[32]

Mexico and Peru and black musicians has occupied the attention of Robert M. Stevenson (see in bibliography). The censuses also occupied the attention of bibliophile A. A. Schomburg, who in 1923 alerted his readers to those published by the Official Center of American Studies at Sevilla [see in Ethnos: revista mensual para la vulgarización de estudios antropológicos sobre México y Centro-America. Tomo I, numero 2 (1950, 50 p)]. Señor Germain La Torre published 3 documents of the census population of the Viceroy of New Spain found in the General Archives of the Indies at Seville (except one) all dating from the XVI century.

The Archbishopric’s of

Mexico noted 10,595 Negro slaves and 1,505 Mulattoes.

Michoacan noted 1,765 Negro slaves and 200 Mulattoes.

Nueva Galicia noted 2,375 Negro saves and 150 Mulattoes.

Tiaxcala noted 2,958 Negro slaves and 100 Mulattoes.

Yucatan noted 265 Negro slaves and 20 Mulattoes.

Oaxaca noted 481 Negro slaves and 30 Mulattoes

Chiapas noted 130 Negro slaves.

Manifestations of their musical proclivity is present but not in abundance.

Contrastingly, the investigation of the earliest black music practices of the United States has been one of the last important frontiers to be scientifically investigated. For example, the Dutch settlements in New Amsterdam a.k.a. New York, were never scrutinized for black musicians.[33] Stereotypes replaced scientific evidence. Music and musicians have also been identified through the medium of American fiction and non-fiction literature and many identities “invented” [viz. Teodora Ginés] These “identities” have no genealogical tracings. Then, too, imaginary dating of specific events was often substituted for the lack of exact methodology (the ethno-musicological approach). Throughout our investigations concerning the origins of black music in American studies,[34] it became apparent that positive identification and investigation of black participants were seemingly neglected areas.

Totally involved in this process were scholars completely divorced from the black society but eager to capitalize upon a “supposed” vacuum of information. Aiding them were libraries which purchased books, often faulty and repetitious, using as an excuse “something is better than nothing.” Unremorseful, they aided and abetted the commercial efforts of American (and some European) publishing houses long noted for exploiting a gullible public by providing incomplete and often false materials with recitative-like summaries.[35] For example the title of a very recently received book Black Africans in Renaissance Europe,[36] attracted our attention only because of the use of the word “renaissance” reflective a rebirth in the fine arts in which period we earned our degree on the musical subject of “The St. Matthew Passion of Metre Jan, maestro di cappella to Hercules II, duke of Ferrara.”[37]

It was hoped that information in that volume would give more enlightenment on the subject of both blacks and their participation in the fine arts. However, according to the introduction a conference was arranged at St. Peter’s College, Oxford in September 2001 with 18 speakers. The range of disciplines were 3 “ordinary” historians, 1 economic historian, 1 church historian and 2 cultural historian, etc. Sadly we could not note any “music” historian! Since music was one of the primary arts during the renaissance period, there should have been some representative from that discipline, especially since our professor and hundred of others had been working for years in the same area.[38]

Unfortunately this work does not transcend other works in rediscovering the identities of artistic blacks although traces of their influence in the works of many renaissance composers and artists have been heralded. In general this work reflected on such subjects as stereotyping, conceptualizing black skin (in England) or the inclusion of black women in the court of Isabella d’Este or slaves in the Lisbon court of Catherine of Austria.

In the introduction entitled “The black presence in Renaissance Europe” it is reported as an area “greatly overlooked” in scholastic studies. We would have preferred the word “under researched” (the half empty of half full theory). The great number of blacks who were brought to the European continent portends that there is sufficient documentation available to discuss who they were and how did they survive in a new land. Although nearly all were servants, the fact that they were mentioned in music and described in paintings broadcasts that material exists about them and their lives.

Also to blame are both black and white scholars (and non-scholars alike) with little expertise in research techniques[39] but eager to become major players in developing a black aesthetic in scholastic activities.[40] Instead of cultivating an atmosphere for a cadre of devoted scholars (not of the peek-a-boo mold) of proven eminence to “assist” in rediscovering, redefining, editing and developing materials pertaining to the black musical experience, they developed only enough materials to assist in self aggrandizement.[41] Most have attempted to substitute 20th century “surmisings” for 18th and 19th century absolutes. Viz. the correct birthplace of Francis B. Johnson (1792-1844)–not the Martinique Islands but in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania!

For example, “Jim Crow” and “Ragtime” are two of the most prominent areas that contain many coon-type images on music sheet covers. From such rag-time examples one might get the impression that all blacks did the cakewalk, the “Pas-Ma-La,” ad infinitum. Perhaps many did participate but the exemplars appear to be but exploitations of a miniscule part of the black music scene. One notes the absence of real faces on the covers suggesting that the publishers were either unable or may have been inhibited in securing real-life persons. Therefore they manufactured countless images depicting the same scene over and over. The medium finally became over saturated and simply dissipated!

Such imagery has produced stereotypes that only have ancestries in fiction!

To challenge such stereotypes we are issuing some music examples composed by black American musicians during the nineteenth century. Time, finances and age prevents us from issuing exemplars of many non-American black musicians. What was done in the past cannot be changed to conform to current music practices. Arrangements of some of this music may be desirable but should be accomplished bearing in mind the authentic intent and spirit of the time when it was written. Novel arrangements may pique the interest of some auditors but are seldom enduring as evidence of genuine talent.

Ethnicity and Genealogy Considered

The best sources for any genealogical information are birth and baptismal records whenever and wherever available. For example the early records of the Dutch churches in New Amsterdam=New York yield information about the 1630-1700 period (the “negar” period). Revisiting material in Canadian records also resulted in surprises (the “sable” or “colour” period)! However, in lieu of the foregoing, the next best materials in America appear to be the United States censuses supplemented with information from city directories, court, institutional and notarial records. The question “Why seek out censuses” for material of value is easily answered in genealogical circles. However, for many people of color, the dates given in these censuses vary for many reasons:

a. most did not have access to vital records

b. those born during the slavery or slightly after the period often had to guess

at their exact birth and even their lineage

c. some changed their birth year and name during the slavery period to

escape future identification from would-be captors.

d. women (and some men) often changed their birth dates so as not to appear

to be older than their husbands

The censuses are therefore one of the more consistent sources to record the “occupations” [N. B.] of its inhabitants.[42] City directories are another source enabling one to fill in data during each decade of the census returns.[43] For many of these hitherto unmentioned musicians who worked in the music field during the 19th century, their commitment to music endeavors surpassed the efforts of transient musicians who after making a few bucks and some notoriety left the field of music without further venerating the profession. In these censuses, one may formulate a proven opinion and statistically prove the totality of the black commitment to professionalism. It is as an economic reality that this important aspect in the study of black music and musicians be further pursued.[44]

The use of censuses (and other official records) provided an opportunity to promote a more exact knowledge of the travails of these musicians and especially their family relationships. Thus information regarding the career of the black violinist, José Redondo Brindis de Salas y Garrido omits the fact lacks information that he received American citizenship in 1883 and his color “black.”. Then, too, the musician who was noted at Falmouth, England, Emidée, has never been fully described except through the account of James Silk Buckingham.[45] However, because more sophisticated technology exists today than some twenty-five years ago when our investigations began original sources have become more accessible.

Thus, in Buckingham’s memoirs it is revealed that Emidée [Emidy] was born in Guinea and sold into slavery by the Portuguese and subsequently taken to Brazil. His master or owner then took him to Lisbon and after realizing the boy’s musical potential supplied him with a teacher. Emidée became proficient enough to perform in the second violin section of the opera orchestra. The ship captain, Sir Edward Pellow or Pellew, needing a good violinist to play for the amusement of his crew of the Indefatigable, visited the opera house and upon hearing the young man arranged for his abduction. Thus Emidée’s enslavement interrupted his academic career. It was only upon Pellow’s appointment to the command of a line-of battle ship, L’Impetueur, was he let ashore at Falmouth where he remained, until his death.

At Falmouth Emidée reentered the concert life and became noted as a teacher of music. In addition he was reportedly the leader of the orchestra of the Harmonic Society of Falmouth. Buckingham secured Emidée as a teacher prior to 1807 at which time Buckingham left Falmouth for London. He submitted some of Emidée’s pieces (quartets, quintets, and symphonies for full orchestra) to Mr. Salomon, one of the principal leaders of concerts at Hanover Square Rooms. Emidée’s quartet, quintet and 2 symphonies were tried and approved. Salomon wanted to bring the black musician to London but this was objected to because “his colour would be so much against him, that there would be a great risk of failure.” However, a private subscription was taken up and sent to Emidée at Falmouth. Thus ends the Buckingham account.

From other sources new materials can now be added. We learn that Emidée’s [now Anglicized to Emedy or Emidy] first name was Joseph (d. April 24, 1835) and married Jennifer [Jane] Hutchins (d. January 24, 1842 in Truro) 16 Sept 1802 at Falmouth. They had six children:

1. Joseph (b. July 23, 1803 – christened 14 August 1803)

2. Thomas H. (b. July 6 1805 – christened 8 December 1805)

3. James (b. July 13, 1807 – christened 11 March 1808)

4. Cecilia (b. Oct 21, 1809 – christened 10 June 1810)

5. Benjamin (b. June 24, 1812 – christened 31 July 1812 – died Aug 3, 1812)

6. Richard (d. 1837)

Joseph, the eldest, moved to Kenwyn and married a woman known as Jane Rose. They had a set of male twins and one female daughter:

1. William (christened 25 December 1829); married one Jane Reed and their daughter

Eliza, born 10 January 1846 at Kenwyn was christened on 8 February 1846 at

Thuro.

2. Richard (christened 25 December 1829) married one Susan and there were two

twin-girls: Clara and Jane, christened 3 October 1862 at Thuro.

3. Eliza Rose (christened 3 January 1830)

It is the family of Thomas, the second son of Emidy whose family attracts attention in American black music studies. He married one Margaret Rose and lived at Kenwyn and sired six children:

1. Cecelia (christened 1 January 1832)

2. Francis Antonio (christened 1 January 1832)

3. Eliza (christened 4 October 1835)

4. Joseph Antonio (christened 4 October 1835)*

5. Richard Samuel (christened 1 August 1837)*

6. William James (christened 3 January 1841)*

In our material on “black minstrels,” we have noted the presence of James and Richard Emily in America. Presumably they are Richard Samuel and William James. However, at the time of Richard’s death in Chicago, November 13, 1885, only his brother J. A. is cited as living in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. Upon examination of the census records of 1880 we do find Joseph A. age 45 musician born in England and is listed as “white.” His age matches that found in the church records at Kenwyn. In his home are Eliza A., age 42 and daughter Julia, 12. Meanwhile Richard’s biography may now be corrected to read born in Kenwyn. His birth is probably correct, June 16, 1837 since he was christened nearly two months later.

Lacking is better documentation on whether William James or Joseph Antonio performed in the various minstrel troupes of that period perhaps masquerading as “slaves of the sunny south.” James [William?] is always given but little else surfaces about him after his brother’s death. Later genealogical records fail to accurately define the descendents of the original Emidée especially Joseph Antonia, b. 1846 -d. 1871 in America (new information in biographical section).

Among the many biographies are musicians whose ancestry admits “negroid” genes. Much too often, these families have so covered their ancestral tracks that unmasking the evidence is nearly impossible. Reasons for faking their identities lies in the social arena which readily accepted genius if white but looked askew is there were traces of black blood [viz. the Lambert family of New Orleans].

In previous years it has been made to appear that fair-skinned blacks were most representative of a greater intelligence. Their darker-skinned brothers of similar intelligence have had to surmount this concept to prove the falsity of the “fair-skinned theory.”

Where possible, we have attempted to bridge this area which also admits black musicians with virtilago or were albinos.

We begin our chronological listing by noting anonymous blacks known to have been involved in music making. Such strands of activity are treated as a separate category in hopes that new information may surface.

Embellishing our text are items of iconographical interest. Pictures and other ephemera were also thought important enough to be included.

Scholars who have materials of their own may probably challenge the faults in our presentation but not its logic! It is important to know that what has been entered in this publication has been personally viewed by this writer. Materials to which we have not actually viewed are therefore not included. However, to those who attempted to aid in this primary work, we express our most sincere gratitude.

Arthur R. LaBrew 1998-2009

——————————————————————–

[1] The idea that black writers do not take the time to research this lineage is refuted in many, many unused and probably unknown publications written by black writers. For example, we may cite the correspondence from the Community Service, 313 Fourth Avenue, New York City) as one such source in 1923. Titled Music Composed by Negroes–Six Famous Colored Composers and a List of Their Productions it named Harry T. Burleigh, Will Marian Cook, S. Coleridge-Taylor, R. Nathaniel Dett, Carl R. Diton, J. Rosamond Johnson and Clarence Cameron White and an impressive list of works undoubtedly taken from publishers catalogs. (See also in The Negro World, May 19, 1923.) Still further was mention of such musicians such as Bridgetower, Brindis de Salas, José White, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges and Samuel Coleridge Taylor. Black owned newspapers (which some black and white writers have but recently “discovered”) also made mention of a myriad of musicians! However, the gathering of this perspective into a single volume first took place in Trotter’s Music and Some Highly Musical People (1878) [whose veracity was known to that generation but further validated for readers of later generations by Robert M. Stevenson] and reinforced in Maud Cuney Hare’s Negro Musicians and Their Music (1936) and lastly Eileen Southern The Music of Black Americans (W. W. Norton & Co.) 1971.

[2] Alfred Einstein. The Italian Madrigal.

[3] Phylon, 5 No. 2 (1944), p. 105-113 and “Exotik in früher Zeit” in Musica 14 (1960), p. 214-219.

[4] Taken from a lecture at the Statutory Meeting of the Vienna Academy of Sciences, May 30, 1920 and translated in the Journal of Negro History VII, 121-132 by Mr. Battiscombe Gunn. He cautions: “The state of affairs must be the result of many migrations and numerous conflicts with varying issues which began in immemorial times and have continued, to a lesser extent, down to the modern period. Of all these events history knows very little [ed. italics]. In the majority of cases it can but argue back from the nature of the results to the anterior stages, and this only for fairly recent epochs.”

[5] African Times and Oriental Review (1912), p. 935. Viz. the treatment of Blind Tom in modern publications!

[6] On Trotter see Stevenson, Robert. “America’s First Black Music Historian” in Journal of the American Musicological Society, 1973. Eileen Southern made her contribution with her The Music of Black Americans (W. W. Norton & Co.) 1971.

[7] Anti-Slavery Opinion in France during the Second half of the Eighteenth Century (John Hopkins Studies in Romance Literatures and Languages Extra volume X, 1937).

[8] See earlier travails of Francisco Curt Lange! In an informal discussion with one well-known white scholar who had written on American music, it was learned that her publication was not reviewed solely on grounds that it contained references to more than five (5) black musicians (academic integrity seems to have been a matter of fleeting concern). Among black scholars, many are quick to make general observations from a battery of incomplete materials! Still further, another scholar suggested writing solely on the life of an anonymous 18th century run-a-way slave knowing that the ravages of time would have made such a task almost impossible!

[9] Carl Diton in his news articles “Sermons” recognized composers who arranged previously written works but venerated such black composers whose works were originally conceived.

[10] N. B. Materials sought by this writer have come primarily from this segment who, in their wisdom, held on to documents in which they were only participants. In dismissing these people, scholars and institutions missed the opportunity of collecting supplementary information found no where else! Those areas which are overstressed are vocal soloists, choral and composers of which 2% may be rated superior, 8% excellent, and more than 75% average to bad!

[11] See African American Music an Introduction (ed. Mellonee V. Burnim and Portia K. Maultsby, Routledge, copyright 2006 by Taylor & Francis Group LC).

[12] For example the information of the actual birth of the eminent black bandmaster Francis Johnson (1792) in a 2006 publication (see African American Music by Mellonee V. Burnim and Portia K. Maultsby) uses the source found in Sam Floyd’s International Dictionary of Black Composers (1999) supposedly researched and written by Stephen Charpíe who extracted this valuable information from this writer’s biography of Johnson (1994). If the editors believed Charpíe’s historical acumen was original then they must also believe his other errors in the same essay!

[13] Courtesy Mrs. George. Music. Collectors such as Thornton Hagert, Robert Montgomery, Manny Kean, Harry Dichter et al. were willing participants as was the music staff of the Library of Congress – Wayne Shirley, Elmer Booze, Willliam Lichtenwanger and John Newsome.

[14] Even more recently, the collection has been made available on Internet. Again caution should be taken for these items represent only materials not made a part of the general music collection.

[15] At our urgings, Sam Dennison (d. 2005), chief of the music division at the Free Public Library, began isolating materials of Philadelphia’s black composers in 1969. Others have since used that material without acknowledging the previous efforts. The New York Public Library has done little towards cataloging its collection since this editor first visited it in 1970. The Grovesner collection at Buffalo, New York still has an amazing amount of material yet to be catalogued. In its favor are over hundreds of bound volumes which are available. The Bly Corning Collection (Ann Arbor, Michigan) still remains unorganized The materials of the Historical Society of Maryland were inaccessible to this writer on September 11, 2001 partially due to the terrorist bombings at New York and Washington, D. C. However, the Enoch Pratt Library and the Peabody Conservatory libraries remained opened to this writer.

[16] In this sense we follow the dictum of our late professor, Gustave Reese, whose disdain for books on aesthetics was well pronounced! In most instances such books often represent a highly introspective approach. Like, Reese, we prefer the “historical” approach that differs from the “ethno-musicological” approach which today so dominates the commercial market in black studies.

[17] We are reminded of the effort of the work of the eminent Karl Geiringer who noted the expression “dictionary-composer” and lamented that the “state of affairs to be unsatisfactory in the case of any composer, certainly calls for a remedy” and began a more thorough investigation on biographical affairs of Mozart’s younger son. See in Musical Quarterly October,1941 Vol. XXVI, No. 4 titled W. A.Mozart the Younger. Even more distressing are errors in Alain Locke’s The Negro and His Music * The Negro Art Past and Present (copyright 1936, the same year as the Hare publication, by the Associates in Negro Folk Education), chapter 5, “Early Negro Musicians,” p. 36-42, in which much of his material is merely “copied” from other unproved sources; viz. the inclusion of Louis Moreau Gottschalk.!

[18] In many black churches the musician, choir director or minister of music does not select the hymns. The chief prelate usually does and is often not familiar with the new hymns. Nor is there any attempt by the music publishers to address this problem undoubtedly hoping that the choir director or minister of music will bring it to the attention of the minister. Those churches who are lucky to have the better type ministers who are perspicacious fare better when they develop a hymn singing church.

[19] Dr. Juan Max Boettner in Musica y Musicos del Paraguay (Edicion de Autores Paraguayos Asociados) speaks only of their folk qualities but names no musicians.

[20] Courtesy Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

[21] Robert M. Stevenson (and his cadre of scholars) has brilliantly introduced us to much information derived from early Portuguese, Spanish and Latin sources in addition to many music exemplars. Viz. “Some Portuguese Sources for Early Brazilian Music History” in Anuario 4 (1968), pp. 1-43 or “A Guide to Caribbean Music History” (1975) et al. For his Portuguese efforts he was knighted by the King of Portugal in 1988.

[22] Stevenson, The Afro-American Musical Legacy (1968); on Black Dances see Inter-American Music Review, IX, p.105-113 and XIII (1993), p. 150 História da música portuguesa by Manuel Carlos de Brito and Luisa Cymbron (Lisbon, Universidade Aberta [Palácio Ceia, Rua da Escola Politécnia, 147, 1200 Lisboa], 187 pp.

[23] See Anonymous Barre prints of 1550 and 1555. Alfred Einstein reports of many black characters in the 16th century moresca repertory in Italy who play lewd, base roles. Then, too, unless one has access to a library rich with available Italian material he/she can only surmise on certain facts such as is found in Rivista Italiano di Musicologia 32 No.2 (1997), p. 349 where it reads “Io Alvise [name] trombon dela ilustrissima Signoria de Venezia schiavo et servo a piedi di questa se richomanch” but does not explain whether “schiavo” means “slave” or is the reference to a black slave and servant. Paul Nettl has noted that the great Orlando di Lasso saw the original ‘moresche’ in Naples and composed some which were produced in Munich. He notes that Sandberger, too, points out such characters as the negresses Giorgia and Lucias and the negro Cuccuruccu (see in Lasso) as examples. More work in the various Italian archives might resolve this and other such related matters.

[24] Sigurd Petterson’s on-line paper Schwarze Militärmusiker zwischen Schmiss und Shmach has brought new information from the German archives.

[25] A notice in Buenos Aires (hacia fines del siglo XVIII) reads: “Los músicos de color: en ese atrayente y provocador finisecular sigly XVIII, luego de labor cumplida por los hombres de la Compañia, en una sociedad con rasgos como los anotados y en una ciudad que pretendía erigirse en foco de América, nos encontramos con un grupo de hombres que fueron representantes valiosos y significativos de la vida musical de la metrópoli. Nadie los amparaba, nadie los protegía, estaban indefensos. Eran los protaganistas de muchas de las perturbaciones que vivió Buenos Aires por entonces. Algunos miembros conspicuos de la Iglesia habían comenzado a no ver muy bien ciertas pretansiones, como la de divertirse bailando fandangos o recreado bailes de carnaval. (12) Una legión de pardos que surgió a la escena de esas manifestaciones del quehacer artístico sólo por la maravillosa disposición natural de la gente de color hacia la música, que es harto conocida. Elinstinto rítmico es admirable, motivo por el que se los asocia y privilegia como protagonistas de manifestaciones musicales de expresión popular. Muy cerca nuestro y en la misma época que nos ocupa, fueron mulatos los creadores del movimieto musical “mineiro”, de Brasil–Minas Gerais–y sus composiciones están muy cerca del preclasicismo europeo. Es la misma época de aquel genio y fenómeno insólito en la historia del arte, el Aleijadinho, hijo de portugués y esclava negra./ Pero si Brasis tuvo un movimiento tan generoso y pródigo, en verdad América toda, desde mediados del siglo XVI conoció un proceso artístico que desde México se extendió por la costa del Pacífico, cubrió la mediterraneidad de Bolivia y con posterior dad llegó hasta el Río de la Plata, donde el negro, el indio, el mestizo, en fin, los pardos, aquellos desposeídos, marginados del poder, perseguidos cony sin causa, fueron los actores por demás valiosos de las manifestaciones musicales desde el inicio hasta el ocaso colonial americano. De un extremo a otro de nuestros territorios dejaron las huellas de su paso en una música de particulardidades bien distintivas. En ese admirable finisecular siglo XVIII, en Buenos Aires, aparecieron músicos como Francisco Asnit, José J. Alzaga, José Basurco, José Chorroarín, Crispín Flores, Feliciano y Francisco Faa, la mayoría, integrantes de la orquestra que desde 1777 dirigía Antonio Belis, (13) y a la que pertenecían además Hipólito Gusmán, Gregorio San Ginés, Ignacio San Martín y algunos de los Pintos,entre los que figuraban Roque Jacinto, Bernardo–profesor de clave en el colegio de la Hermandad de la Caridad (14)–y José Sebastián/Ana María Rodríguez ere el organista de la Catedral. (16) De la misma época fueron instrumentistas activos Francisco Pozo, Nolasco, Juan Rodríguez Lisboa, Francisco Solano y su hijo Borja, Vicente de los Santos, Ignacio Azurica–hijo de cacique-autor de motetes y organista de la Catedra. (17) si nos adentráramos en el siglo XIX, porríamos llegar at la fugura del aplaudio mulato José A. Viera, aquel que protagonizó el don Bartolo del Barbero de Sevilla y gue cantó de manera admirable según la crítica de entonces, a pesar de algunos juicios poco favorables relacionados con “el manejo de su persona”. (18).

[26] In meeting Dr. Lange [1903-1997, d. in Montevideo, Uruguay] in Venezuela (1988), he expressed that he could not explain how these black musicians received their schooling in European musics. His untiring efforts on their behalf remains the most significant re-discovery of the century. His publications will remain monumental!

[27] Donald Ramos, “Community, Control and Acculturation: A Case Study of Slavery in Eighteenth Century Brazil,” in The Americas 42, 1986, No. 4, p. 421.

[28] In 1738 a majority of the slaves were of Gold Coast origin but by 1804 a shift noted a overwhelming majority of Bantu.

[29] Candombles are one of the earliest sexual kind of dance noted in the early years.

[30] In a dispute between the white and black members, the whites were expelled in 1733. The whites went to the church of Padre Faira and founded their own brotherhood of Nossa Senhora do Rosário.

[31] This brotherhood split into two groups in the 1740s one going to the parish church of Dias and the other built its own church in the parish of Ouro Prêto.

[32] Viz. Candombles fn. 29.

[33] See Anthony (1640s). Most publications have only recognized blacks in the southern colonies, viz. Virginia!

[34] Elizabeth T. Greenfield: The Black Swan (89pp.) 1969, Part 1; Elizabeth T. Greenfield: The Black Swan (264pp.), 1982, Part 2; Francis Johnson 1792-1844 (41pp.), 1974; Selected Works of Francis Johnson (133pp.) 1976; Two Lectures: (1) Black Composers of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Before the Civil War for the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Philadelphia, 1974; (2) Black Musicians of and in the New World: The Exodus to Europe (63pp), 1974 for the Latin American Session of the American Musicological Society, Washington, D. C.; Black Musicians of the Colonial Period (181pp.), 1976, 1977, 1981; Before and After Ragtime (Detroit, Michigan, lecture, 35pp.), 1978; STUDIES IN NINETEENTH CENTURY AFRO-AMERICAN MUSIC (Series 1): Chapter 1 The Image of Blacks as Seen in Music Literature — A world perspective (in progress); Chapter 2 Black Music and Musical Taste in New York City 1800-1850 (113pp.), 1983; Chapter 3 The Underground Musical Traditions of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1800-1900 (347pp.), 1983; Chapter 4 Black Music in the Northwest Territory— Detroit, Michigan from 1835-1900 (in preparation); Chapter 5 Captain Francis Johnson (1792-1844) Great American Black Bandsman, Life and Works in 2 volumes (volume 1, 1994), 550pp; Chapter 6 Boston: Music In An Abolitionist State from 1800-1890 (approx,. 250pp.), 1984; Chapter 7 Black Music in a Slave State: Nineteenth Century New Orleans Before Storyville (550pp.) 1988-1994; Chapter 8; Marie Selika – American’s First Great Black Coloratura Soprano (in preparation); Chapter 9; Cartoons, Blues, Black Minstrelsy, Bands, Operatic and Concert Troupes, Black Opera (in final preparation); Chapter 10 Free At Last: Legal Aspects of the Career of Blind Tom Bethune (reissue of 1976 report with new additions and pertinent observations) (in preparation); STUDIES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AFRO-AMERICAN MUSIC (Series 2): The Afro-American Music Legacy in Michigan (191pp.), 1987 (illustrated) – Supported by the Michigan and Detroit Councils for the Arts for the Sesquicentennial celebration of the State of Michigan, biographical materials of black musicians during the nineteenth-century are thoroughly detailed (Detroit, 1987, limited edition); Vignettes of Black Musicians in Detroit and its Surrounding Area 1900-1988 (Detroit, 1988), 251pp.; They Too Shall Pass – Biographies of Older Detroit Musicians Deceased or in Advanced Age (Detroit, 1990), 150 pp.; AFRO-AMERICAN MUSIC REVIEW (Published by the Michigan Music Research Center, Inc.); Volume 1, No. 1 (July-December, 1981): The Caribbean and Latin American Influence of Black Musicians Abroad and in the United States; Tribute: Elizabeth T. Greenfield; Articles: The Brindis de Salas Family, Julian, Nicasio and Manuel Jiménez family, Doña Maria Martínez. Special feature “Additional Notes on Blind Tom Bethune and His Music. Review: George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower, 1788-1860 (with additional notes on Chevalier de Saint-Georges); Volume 1, No. 2 (January-June, 1984): Tributes: Melvin Charlton (1880-1973), Edgar Rogie Clark (1913-1978) and Edward Hammond Boatner (1897-1981); Articles: “150 Years with the Lambert Family of New Orleans;” Edmond Dédé (dit Charentos) 1827-1901, Eugene Arcade Dédé 1867-after 1912; Special features: The Writings of Don Lee White; Two New Works of Samuel Snaër (1832-1896); Musicien Extraordinaire: Henrí Salvador of Paris, France (1917-); Volume 2, No. 1 (January-June, 1982): Tribute: R. Nathaniel Dett; Biographical: Black Musicians of the Colonial Period and Their Successors (1652-1829); Supplement 1: Run-Away White Musicians in Colonial America 1729-1801; Musicians in the United States Colored Regiments — Civil War (Part I, A-L); Special features: An Unknown Source for the Hidden Afro-American Musician’s History — William Pleasant (1856-1880); Biographical Notices to the Harmon Foundation Awards (1926-1930); Volume 2, No. 2 (July-December, 1985): Perspectives in Black Music Studies — A Review of Eileen Southern’s Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians; Volume 3, No. 1 (July-December, 1985): Tributes to James Monroe Trotter: Notes Toward a History of Music in Louisville, Kentucky 1840-1897; — A Nineteenth Century Afro-American Singing Convention in Abbeville, South Carolina 1887, 1888, 1889; Articles: Hymnology Among America’s Early Black communities 1770s ca. 1855; The Gillams of Detroit, Michigan; Black Opera — Myth or Reality?; The Carolina Singers — Philadelphia Spirituelles of 1872 (facsimile of music texts); Volume 3, No. 2 (January-June, 1986): The Music of Jacob Sawyer, facsimile edition of spirituals and minstrel music no longer available; Volume 4, No. 1 (July-December, 1986): International Dictionary of Musicians of Color, Index. The Bantu Musicians of South Africa, Index; Volume 4, No. 2 (January-June, 1987): List of Black Violinists and Fiddlers in America 1678-1800, 97pp. (Detroit, 1987); Volume 5, No. 1 (July-December, 1993): Dictionary of Black Musicians and family relationships found in United States Censuses and other Records 1800-1900 including their Music Publications retitled International Dictionary of Musicians of Color and family relationships found in various sources: Antiquity to the end of the Nineteenth Century including their Music Publications (planned for 1998-2000); Volume 5, No. 2 (January-June, 1994): Trotter Vindicated? An occasional paper on America’s First Black Music Historian (1994) 148pp.; Volume 6, No. 1 (January-June, 1996): Report:Banneker Institute ca. 1853-1860 “Credo” for a New Century; William Appo (1808-1880); Roland Hayes In Detroit During the ‘20s; Fifty Years of Programs Given in Memory of the E. Azalia Hackley Collection,1943-1994; Organist Extraordinare: David Hurd; Necrology: Joseph Hayes (1920-1995); Leroy Boyd (d. 1996); John D. Carter (1932-1981); Dorris Berry (1930-1994); Volume 6, No. 2 (July-December, 1998) No. 2. Biographical: Francis Johnson as a Musical Ambassador; Joshua Saddler, Violinist, Musician; For Future Reference: Blacks in the Military: United States Colored Regiments-Civil War, Part II M-Z; More Spanish Dances and Latin Tinged Compositions in Amercia before 1850; Reference: The Colored Theatrical Guide and Business Directory of the U. S. (1915); Editorial: Untapped Resources For Studying The Plight of Black Composers in the United States.

[35] Some important writers and scholars have refused to utilize commercial publishing ventures and effected their own independent publishing sources. For example Hendersonia: The Music of Fletcher Henderson and His Musicians by Walter C. Allen (Highland Park, New Jersey, 1973) a detailed study of Fletcher Henderson is one of many brilliant examples.

[36] Cambridge University Press (2005), edited by T. F. Earle and K. J. P. Lowe.

[37] Manhattan School of Music, 1955, under Gustave Reese.