Prof. Arthur LaBrew, Musicologist

Anonymous

Anonymous (1570‑1520 B. C.)

Dancers.

[Image II, plate 51]

Anonymous (1504‑1450 B. C.)

Dancers and drummers in military expedition returning to Egypt from the Upper Nile (Dynasty XVIII).

[Image II, plates 29‑31]

Anonymous (1425‑1408 B. C.)

Young black dancers.

[Image II, plate 54]

Anonymous (1342‑1333 B. C.)

Dancers and trumpeters in procession of Amun (Dynasty XVII).

[Image I, plate 32]

Anonymous (Hellenistic Period)

Bronze statue of male black dancer. Muse Archeologico Nazionale, Italy.

[Image II, plate 269]

Anonymous (Hellenistic Period)

Statuette of dancer (?). Baltimore Walters Art Gallery.

[Image II, plate 270]

Anonymous (300 B. C.)

Woman dancing. Terracotta. Ruvo, Museo Jatta.

[Image II, plates 219‑220]

Anonymous (400 B. C.)

Negro trumpeter on shield of warrior dating from 5th century B. C.

[Snowden]

Anonymous (100 A. D.)

Black musicians performing on flute and sticks in front of a nilometer. Photograph taken from the Lepcis Magna, House of the Nile. II century A. A. Tripoli, Archaeological Museum. Mosaic (detail).

[Image, Egypt]

Anonymous (618‑907 A. D.)

Slavery in China during the T’ang dynasty (A. D. 618-907). “Dancing girls imported from regions even farther west performed novel Iranian dances and were probably slaves. Dark-skinned K’un-lun slaves, certainly negroid, were very popular and references to them go back to the fourth and fifth centuries. In T’ang times some K’un-lun slaves may have been African negroes imported by Arab traders.” J. A. Rodgers discovered an item carried in the New York Times November 26, 1933 which mentions Dr. Joseph F. Rock’s 3-volume book on the little known Na-khi tribe of far South China. This Viennese-born writer had penetrated into the territory near the border of Tibet about 1923 and discovered the “Nakhim,” or “Black People” which he described as one of the most extraordinary surviving races or tribes. He estimated their number at about 200,000 boasting a culture at least 2,000 years old.

[Prof. Chang Hsing‑lang “The Importation of negro Slaves to China under the T’ang Dynasty, A. D. 618‑907,” Bulletin of the Catholic University of Peking 7 (1930), pp. 37-59; L. C. Goodrich, “Negroes in China, Bulletin of the Catholic University of Peking 8 (1931), pp. 137-139; Clarence Martin Wilbur, Slavery in China during the Former Han dynasty, 206 B. C.-A.D. 25 (New York, Russell and Russell, 1967), p. 93; J. A. Rogers, 100 Facts item 17; see Joseph Francis Charles Rock (1884-1962) The ancient Na-khi Kingdom of southwest China Vol. 1 (Harvard University Press, 1947, 274pp., illus., under the title Harvard-Yenching Institute monograph series; 8 and 9 (Vol., pp. 275-554]

Anonymous (724 A. D.)

Musicians noted on the isle of Sumatra.

[André Schaeffner “Ethnologie musicale ou musicologie comparée?” in Les Colloques de Wégimont (Brussels: Elsevier, 1956), p. 22 cited in Robert Stevenson, Inter-American Music Review, XII (1991), 102, fn. 3 previously cited in “The Afro-American Music Legacy to 1800” in Music Quarterly, LIV/4 (October 1968), pp. 475-502]

¬Anonymous (1035)

Blacks appear in England.

[Miniature in the “Chroniques de Norman-die,” a manuscript of the fifteenth Century, in the Library of M. Ambroise Firmin Didot]

Anonymous (1194‑1250)

Germany. Under Frederick II, “negro boys between 16 and 20 were selected to form a musical corps; they were taught to blow small and large silver trumpets.

[Kantorowicz Frederick]

Anonymous (1239)

Trumpeters. The tradition [of a black orchestra in Portugal] was an old one: a writ dated 28 November 1239 gave orders to send from Palermo five young black slaves, sixteen to twenty years old, to sound the trumpets at the royal court. About 713, the Moors had conquered Portugal thus accounting for the presence of black slaves. The market for slaves in Italy increased after the Turks effectively ended the flow from the Black Sea countries in 1453. Some scholars have evidence that most blacks in Italy were acquired from North African merchants who had gotten them from central Africa, via the trans‑Saharan route. About 1565, many of the blacks in Palermo had been brought from Bornu.[1]

[A. Franchina (ed.), “Un censimento di schiavi nel 1565,” Archivio Storico Siciliano, NS, xxxii (1907), 383‑5; Palermo, Italy; in Sicily the slaves numbered about 4% of the population, an estimated 50,000 out of a total population of 1,220,000 in 1535; see in Annali del Mezzogiorno, III (1693), 30‑3 and D. Gioffre, Il mercato degli schiavi a Genova nel secolo XV, p. 34]

Anonymous (1284‑1295)

Moorish drummers & trumpeters at Castile.

[Hilgarth; further G. Scelle Histoire politique de la traite negriere aux Indes Castille and F. P. Bowser The African Slave in Colonial Peru, 1524‑1650]

Anonymous (1291‑1327)

Trumpets. Jaime II’s son entered Toledo accompanied by 100 Moorish trumpets.

[Hilgarth]

Anonymous (1300)

Instrumentalists. Black musician performing at banquet of the Great Kahn. Instruments include cymbals, tambourines, organ and trumpets.

[Image: See in Tractus de septem vitus, fol. 13r, Genoa. London British Museum]

Anonymous (1385)

Citern (?) player. On portion of a tapestry devoted to the Worthies [detail]. At Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

[Image II]

Item (1393-1401ca.)

During the last years of the fourteenth century, the Church in Seville, under Archbishop Gonzalo de Mena, established the hospital of Our Lady of the Angels in the parish of San Bernardo to service the Black population. Somewhat later it moved to incorporate a Negro religious confraternity to run the hospital. The Duke of Medina Sidonia, at his death in 1463 endowed the hospitals with, 1,000 marvadedis. During the same period, the authorities tried “to ease the rigors of servile life by allowing the Negroes certain privileges, such as the right to gather together on feast days and perform their own dances and songs. Eventually it became customary for one of them to be named by city officials as mayoral (steward) over the rest, with authority to protect them against their masters, defend them before the courts of law, and settle their quarrels.” Popular dances were guineo, ye-ye and zarambeque.

[Pike “Sevillian Society” in HAARH 47, 1967, 344-59]

Item (1410)

Negroes in Andalusia.

Mucho antes de Colon, los negros eran tan numerosos en Andalusia, que hasta se organizo una cofradia de negros en la Catedral de Sevilla en 1410. A nadie que este familiarizado con la expansion colonial espanola se necesita recordarle que Mexico, Peru, Guatemala y otras colonias espanolas ricas rescibieron grandes importaciones de negros destinados a realizar tareas que los indio no podian, o no querian llevar a cabo.

[Seville, Spain; see Stevenson, “Acentos Folkloricos en la Musica Mexicana Temporana,” in Heterofonia, Marzo‑Abril, 1977, Vol. X No. 2, p. 51]

Anonymous (XV Century, late)

Trumpeter featured in “Triumph of Julius Caesar” in Romuleon, fol. 170r. Paris Bibliotheque de l’Arsenal.

[Image II, plate 202]

Anonymous (1444/55ca.)

“The women of this country are very pleasant and light‑hearted, ready to sing and to dance, especially the young girls. They dance, however, only at night by the light of the moon. Their dances are very different from ours . . . In this country they have no musical instruments of any kind, save two: the one is a large Moorish ‘tanbuchi’, which we style a big drum; the other is after the fashion of a viol, but it has however, two strings only, and is played with the fingers, so that it is a simple rough affair and of no account.

[Alvise da Mosto or Cadimosto (Venetian) The Voyages of Cadamosto, Hakluyt Society, Hakluyt Society, Series 2, LXXX (1937), Chapter XXXIII, p. 50f.; Robert Stevenson Inter-American Music Review, XII (1991), 103, col. 2; first published in 1507 Le navigazioni atlantiche del Veneziano Alvise Da Mosto, ed. by Tullia Gasparrini Leporace (Rome, 1966); English translation by Robert Kerr, A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels (Edinburgh, 1824, II, 235-236.]

Anonymous (1451)

Dancers. Black Canarian celebrations in Lisbon in honor of the marriage by proxy of the Infanta D. Leonor to Emperor Friederich III. Some of the entertainment was a mock battle with a war – elephant.

[Stevenson “Some Portugues Sources” in Anuario (1968); Saunders Black Slaves, =Valckenstein, ‘Historia Desponsationis,’ in Caetano de Sousa, Provas, I, liv. III, pp. 608, 611, 613, Lisbon, Portugal]

Anonymous (1470‑80)

Musician from “Crucifixion.” Providence Museum of Art, R.H. School of Design.

[Image, plate 203]

Anonymous (1476)

Three (3) Negro boys instructed in singing by Johannes Urrede who was paid 17,000 marvadedis plus 50 measures of wheat for his care of the three boys, he received an additional 78 marvadedis daily allowance.

[Spain, Stevenson “Spanish Music” reported in MME, I, 126; mentioned in Reese Renaissance, p. 581]

Item (1460? ca.)

The earliest documented black confraternity in Portugal is presumably the Irmandade de Nossa Senhora do Rosario dos Homen Pretos whose “compromisso”, dated December 2, 1565, gives its origin in the year 1460. It is documented by the year 1494 when the king spoke well of the works done by the black brothers while forbidding any threatening move to wrest their control (item dated September 28, 1494).

[Saunders Black Slaves; communication with author]

Anonymous (1461)

Town representatives object to blacks of Santarem celebrating Sundays and religious festivals by inviting other blacks to a feast.

[Saunders Black Slaves; adjudged by L. Leitão, Cortes do Reino de Portugal, p. 227 to be from the Cortes of Evora, 1461]

¬Anonymous (1480)

Two Negro female trumpeters serve the Amazon Queen. [Amazons] . . . they which are not far from Guiana do accompanie with men but once a yeare, & for the time of one month, which I gather by their relation (?) to be in April. At that time all the Kings of the borders assemble, & the Queenes of the Amazons, & after the Queens have chosen the rest cast their lot for their Valentines: This one moneth, they feast, daunce, & drink of their wines in abundance, & the moone being done, they all depart to their own Provinces.

[Amazonia. Ethiopia. Les Secrets de l’histoire naturelle contenant les merveilles et choses mémorables du monde. Franca, ca. 1480. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Départment des Manuscrits, MS. fr. 22971, fols. 2r and 20r (details); The Discoverie of the large & bewtiful Empire of Guiana [1595] by Sir Walter Raleigh, Imprinted at London by Robert Robinson, 1596, Ed. V. T. Harlow, M.A., B. Litt (1928), The Argonaut Press, London p. 26]

Anonymous (1482)

Musicians. King, D. João (1481‑95), succeeding to the Kingdom on the death of his father, D. Afonso, sent forthwith a great fleet to Guine to build the castle, which we now call S. Jorge da Mina, of which Fleet Diogo de Azambuja (1432‑1518) was the Captain‑Major: and how he met Caramanca, Lord of that place.(“As soon as this mass [the first in those parts of Ethiopia] was said, on the day of S. Sebastião, (in whose memory this name was given to a valley in which ran a brook, where they first landed), Diogo de Azambuja drew up his men in ranks [with his trumpets, tambourines and drums, and all in an act of peace] to await Caramanca who had just left his village. . . With the men drawn up in ranks, a long broad way was made, up which Caramanca [probably a corruption of Kwamin Ansa, i.e., King Ansa], who also wished to display his standing, came with many people in war‑like manner, with a great hub‑bub of kettle‑drums, trumpets, bells, and other instruments [bugles, bells and horns], more deafening than pleasing to the ear.” “Gemma Phrisius writeth that in certaine parts of Africa, as in Atlas the greater, the aire in the night season is seene shining, with many strange fires and flames rising in manner as high as the moone; and that in the element are sometime heard, as it were, the sound of pipes, trumpets and drummes; which noises may perhaps be caused by the vehement and sundry motions of such firie exhalations in the aire, as we see the like in many experiences, wrought by fire, aire and winde.” [p. 341; Aethiopia Interior]

[Europeans in West Africa, 1450‑1560 (Transl. & ed. John Willilam Blake, M.A. (2 vols.) London Printed for the Hakluyt Society (1942) 70‑73; The Voyages of Cadamosto, Hakluyt Society, Series 2, LXXX (1937)]

Item. (1488)

One hundred Moorish slaves sent to Pope Inocenio VIII by the Catholic kings.

[Diggs]

Anonymous (1488)

Two years after Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope, João II arranged for the wedding at Évora of his son, Alfonso, marrying a daughter of the Catholic Kings) to include a tableau headed by the Guinea sovereign (Bemoym) attended by 200 blackened dancers dangling golden jingles.

[Stevenson. Inter-American Music Review, XIII (1993), No. 2, p. 150, taken from História de música portuguesa by Manuel Carlos de Brito and Luísa Cymbron]

Anonymous (1491)

Portuguese find African instruments attractive.

[Ruy de Pina, Chronica d’El Rei Dom João II, cited in Stevenson, Inter-American Music Review, XII (1991), p. 103, note 9; XIII (1993, No. 2, p. 150)]

Anonymous (1493)

Detail of a black man playing pipe and tabor; painting by Master of Frankfurt entitled “The Archer’s Festival in the Garden of their Guild.”

[Le siècle de Bruegel: la peinture en Belgique au XVIe siècle (Brussels, 1963), pp. 172-3 and figure 9; Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Inv. 529]

Anonymous (1497)

Flutes; four musicians performing “accordingly with foure sundry voices.”

[Hottentots/Africa; Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, Chapter III of Historia do descobrimento & conquista da India (Combrai, 1551 and 1554 editions); translated as The first Booke of the Historie of the discouerie and Conquest of the East Indias (London: T. East, 1582); Stevenson Inter-American Music Review VIII (1987), p. 98 and XII (1991]

Anonymous (15??)

The Lisbon Igreja de Madre de Deus contains a sixteenth-century panel showing a group of 6 Blacks four playing shawms oneand a sackbut and one unidentified.

[Stevenson. Inter-American Music Review XIII (1993), p. 150, taken from História de música portuguesa by Manuel Carlos de Brito and Luísa Cymbron; see Anonymous 1520]

Anonymous (15??)

Negro performing on a trombono.

[Italy; see in Lacroix’s Arts de la Renaissance and Paul Veronese’s (1528‑1588) “Marriage (of) at Cana” (not the picture in Salon Carre in Louvre; Grove 3rd edition, 1938 under ‘trombone’]

Anonymous (1505)

Drummer in Edinburgh who “devised a dance with 12 performers.

[Staying Power: A History of Blacks in Britain by Peter Fryer (Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey (1984), p. 2.

Anonymous (1509)

Trumpeters. 4 black trumpeters and 1 drummer in Africa pictured in Balthasar Springer’s 1508 account by Hans Burgkmair (1473‑ 1531); see also in Le Relationi

(Vniversali di Giovanni Botero Benese, Divise in Setti Part I; “et in questa nostra Quinta Impressione ristampate, & ricorrette. In Venetia, Presso Allesandro Vecchi. MDCXXII ‑ Plates from Aggivnta Alla Qvarta Parte dell’Indie, Del Sig. Giovanni Botero Benese (1623). Copy at the Library Company of Philadelphia 13219 Q.

[Image II, plate 260]

Anonymous (1509/10)

Negro cymbalist carries pair of kettle drums on his back while a drummer stands behind him beating on the drum (see also John Blanke*).

[England; see in Farmer]

Black confraternity formed in Evora, Portugal. Sasek (see in bibliography) estimates approximately 3,000 black and Moorish slaves in Evora in 1466; see further under Benedetto, Saint*.

[Saunders Black Slaves]

¬Anonymous (1520)

Group of six black musicians; detail from the Marriage of St. Ursula to Prince Conan (see following page).

[See in Stevenson “Brazilian Music History;” Portugal ca. 1520. Lisbon Igreja da Madre de Deus]

Anonymous (1521)

The black brothers of the Rosary presented a short play (entremes) when King Manuel entered Lisbon with his new queen and their musical skills, however, were most in demand. [Stevenson; Saunders Black Slaves]

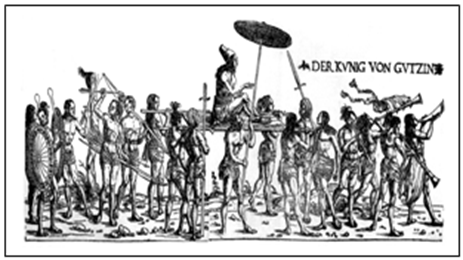

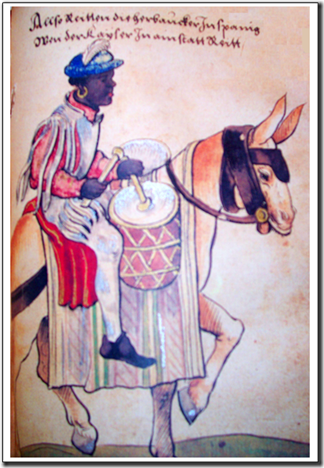

Anonymous (1529)→

Drummer featured in drawing entitled “Drummer at the Entrance of the Emperor.”

[Theodor Hampe. “Das Trachtenbuch des Chritoph Weiditz von seinen Reisen nach Spanien (1529) und Niederlanden (1531/32)” Berlin and Leipzic, 1927), plate check XLVII, LXIII, LXIV, LXV, LXVI]

[Possible black dancing the morisca]

Anonymous (1531‑37)

Slave men and women engaged as singers at the court in Songhay. Askia Muhammad Bunkan (see dates above) reportedly introduced many innovations at his court including some new musical instruments and singers both male and female. That they were slaves is confirmed by the words “qayn” and “qayna”.

[Willis Slaves and Slavery in Muslim Africa, II, 22]

Anonymous (1532)

Although Columbia (Latin America) could note the following musicians on September 5, 1513: Jorge Gutierrez, Pascual de Olias, Francisco Gomez, Eugenio Gutierrez, Juan de Pliego, Fernando de Vega (trompetas), Fernando, Miguel, Diego, Juan de Audinete (trombetas), Alonso Barba (tamborino), Francisco de Visera (gaitero y xabeba), Maestre Pedro Valenciano (tanedor de arpa), Juan Martinez Cabrita and Martin Solano Pizarro (atambors), none can be identified as black or “negro.” However by September 23, 1532, the records could indicate “bailar y cantar y taner” of the Indians, it likewise mentioned “E iban tanendo delante de los dichos negros con los atabales y otros instrumentos, y entrados en la iglesia se hincaron todos de rodillas, viendo que asi lo hacien los cristianos.”

[Documentos Ineditos para la Historia de Columbia (1509‑1550) p. 44f.; U. of M.; U of D, F2257.F7 vols. 1-10]

Item. (1540)

Negroes used as printing assistants by printer Juan Cromberger [d. 1540]; possibly pulled sheets from the press; by 1565 Seville had some 6,327 slaves (who appear to be black) out of a total population of 85,538. See also a list of instruments from Ethiopia in Álvares.

[Stevenson Mexico; A. Dominguez Ortiz “La esclavitud en Castilla durante la Edad Moderna,” in Estudios de Historia Social de España, II (1952), 377‑8); Seville, Spain; Francisco Álvares:Do Preste Joam das Indias: Verdadera Informaçam das Terras do Preste Joam (Lisbon, 1540, folio 136r.]

Anonymous (1541‑43)

Letters of and to the King of Abyssinia.

“I made Ayres Dias (mulatto), whom the people of this country call Marcos, Captain of the one hundred and thirty Portuguese, in place of D. Christovão, and all the Franks were satisfied . . . D. Christovão with four hundred Franks could not destroy the Moors; the fortunate Ayres Dias, his servant, with one hundred and thirty Franks, defeated and destroyed them entirely, although D. Christovão had fought very valiantly against the Moors. . . I made Ayres Dias great among my people, and gave him valuable estates . . . he had come to this country of Ethiopia in the time of the King, my father, Wanag Sagad. . . after the death of Ayres Dias [ca. 1548/50], I appointed Gaspar de Sousa in his place.”

[The Portuguese Expedition to Abyssinia in 1541‑43, as narrated by Castanhoso (trans. & ed. by R. S. Whiteway) London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society (1902), 117ff, 184ff.]

Anonymous (1542‑1553)

[See A. Nobre de Gusmão Cantores e musicos en Evora nos años de 1542 a 1553 for evidences of black performers; particularly note the terms “moriscos”, “pardos,” “morenos,” “ladinos” etc. Anais Academia portuguesa da historia, XIV (1964), 95; see further Stevenson Journal of the American Portuguese Culture(?) Society, iv (1970), 1, 49]

Anonymous fl. before 1547‑56)

Trombeiro (=trumpeter) slave buried by the Misericordia of Evora, Portugal.

[Saunders Black Slaves]

Anonymous (1547)

Pedro de Mandrill (Mandrid?), a Benin black who belonged to the musician Diego de Mandrill, ANTT. Ch. J. III, 2, f. 173, 21 Dec. 1547, published in F. M. de Sousa Viterbo (ed.), ‘Subsidios para a Historia da Musica em Portugal’, O Instituto, LXXX (1930), 500.

[Saunders Black Slaves]

[1] See Missions to the Niger II The Bornu Mission (1822-1825) Part II Ed. E. W. Bovill (Cambridge Published for the Hakluyt Society, 1966).

Recent Comments