Controversial Vaccine Mandates put the Solicitor General’s Institutional Influence to the Test

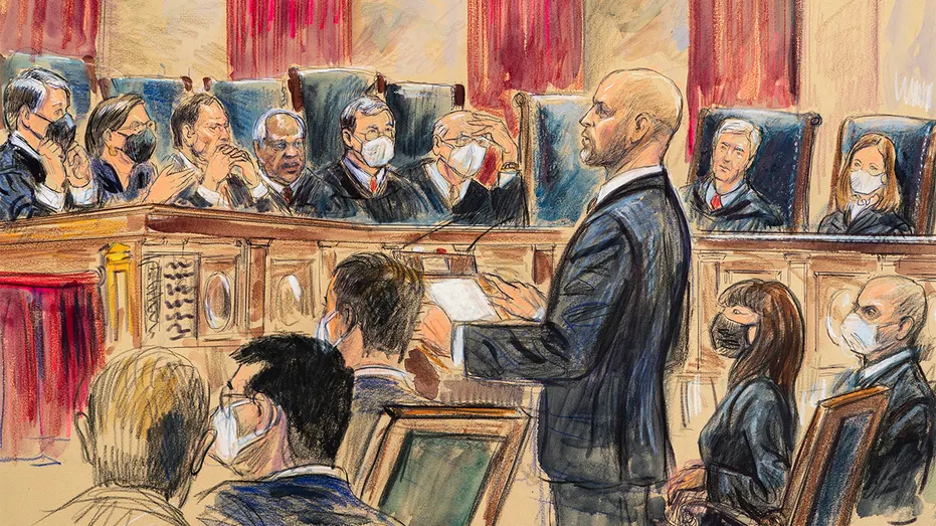

This artist sketch depicts lawyer Scott Keller arguing before the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of the more than two dozen business groups requesting an immediate order from the Court to freeze a Biden administration mandate imposing mandatory vaccine-or-testing requirements on businesses

The United States Solicitor General (SG) operates as the focal point of facilitating smooth relations between a sitting President and the Supreme Court. As fourth in command at the Department of Justice, the Solicitor General is tasked with representing the federal government in virtually every case brought before the Supreme Court. The Solicitor General operates as the primary representor and defender of executive branch policies before the Court, with a history of heightened success in winning the majority of cases he participates in a given year. This is largely attributed to the Solicitor General’s reputable institutional influence (which scholars term as a “built-in advantage”), which grants the SG the advantage of wielding extensive governmental resources, specialized legal expertise, respect from the Court, and reputable status within the Department of Justice to represent the various interests of the executive branch. Because of the Solicitor General’s important functions and positional prestige, the Supreme Court also relies on their expert judgement in cases where the government is not a direct party, allowing the SG to submit amicus curiae(“friend of the Court”) briefs on behalf of the President, an administrative agency, or a concerned member of Congress.

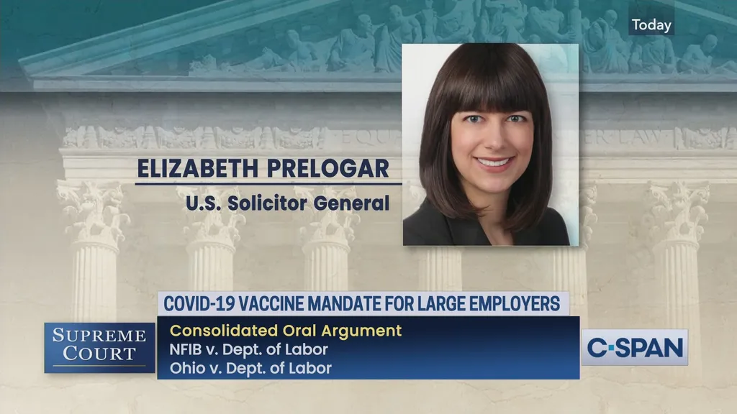

As a “repeat player” who frequently appears before the Supreme Court, the Solicitor General’s success rate is virtually unmatched when compared to nongovernmental litigants. Despite this, there are instances, even in cases bearing great political significance, where the Solicitor General often loses. A recent example can be seen with the Biden Administration’s notable loss in the case of National Federation of Independent Business vs. OSHA (2022), where the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) emergency rule forcing businesses with more than 100 employees to ensure workers are vaccinated or else administer weekly Covid tests, was struck down by the Supreme Court in a 6-3 decision, rendered along ideological lines. If upheld, the OSHA mandate would have impacted more than 80 million workers. In the case, Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar relied on the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 as a defense for OSHA’s perceived authority to regulate the workplace for preventing the spread of Covid-19.

Prelogar argued that this Act grants OSHA the ability to impose rules that prevent further spread of an infectious disease, while best ensuring that businesses prevent further loss of life through mandatory employee vaccination. The Court issued a rare rebuke to arguments presented by the Solicitor General in defense of a direct agency action sanctioned by Congressional statute, generally an area in which the Court is deferential to the actions taken by the government operating within its sphere of influence. While Prelogar, acknowledged that OSHA is limited to regulating only “work-related” dangers, her argument that the risk of contracting Covid-19 constituted such a prevalent danger in workplace environments was completely denied by the Court, which ruled that the virus was not an occupational hazard existent in most workplaces.

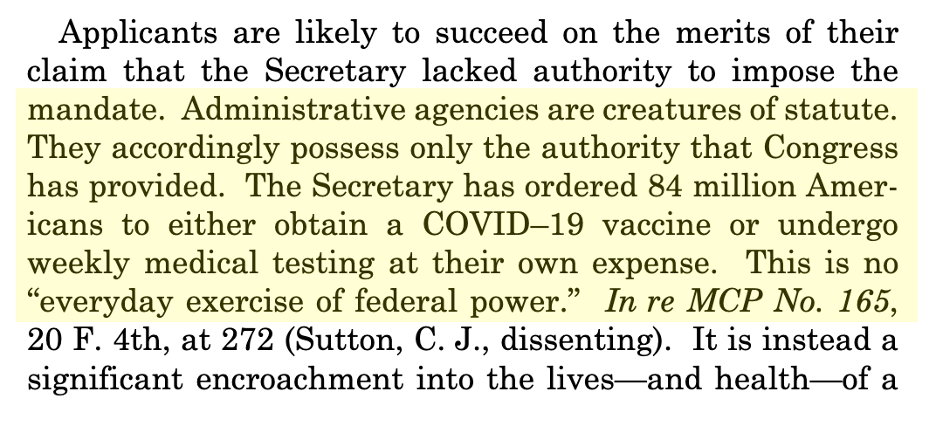

In its per curiam opinion, the Court’s reasoning behind rejecting the government’s stance was that OSHA’s actions we inconsistent with the authority originally granted to it by Congress, intending for OSHA to regulate only hazards restricted to the workplace setting. The ongoing threat posed by Covid-19 was universal, designated as one of the many “day-to-day dangers that all face,” no different from crime, air pollution or various other airborne illnesses. According to the Court, “permitting OSHA to regulate the hazards of daily life—simply because most Americans have jobs and face those same risks while on the clock—would significantly expand OSHA’s regulatory authority without clear congressional authorization.”

The vaccine mandate that OSHA imposed was unlike the usual, and often temporary, workplace regulations enforced by the agency; once injected, a vaccine cannot be undone, and it went well beyond the scope of what OSHA was created for when it sought to have 84 million Americans vaccinated in response to a global pandemic. Despite this, the Court did believe that federal healthcare researchers and workers who engage with Covid-19 on a regular basis should be confined to abiding by such regulations.

This reasoning motivated the Court to issue a parallel ruling on the same day in Biden v. Missouri that permitted a vaccination mandate from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for health-care employees working at 76,000 federally funded facilities. The Court found that vaccinations against a host of other diseases were generally mandatory for healthcare workers across the nation, and that such a requirement for Covid-19 was permissible for preventing its infectious spread among federal healthcare officials.

While the outcome of the Biden v. Missouri case represents how the Solicitor General is largely successful in defending the institutional actions of the federal government when an executive branch cabinet member operates within the scope of their defined or implied powers, the NFIB v. OSHA case revealed the limits of the Solicitor General’s ability to influence the Court to permit agency action when OSHA sought to operate beyond the confines of its statutory authority. The OSHA case presents a strong defense against governmental overreach to mitigate a public viral threat in a private corporate setting, insulating such entities from adherence to overtly broad and invasive vaccine mandates. These parallel cases provide unique insight into both the success of the Solicitor General’s institutional influence with the Court and its ever-present limitations on defending governmental dominion over private affairs.

Category: Socrates Corner