Revisiting the exciting travels of Marco Polo—850 years later, Part II

“I believe it was God’s will that we should come back, so that men might know the things that are in the world, since, as we have said in the first chapter of this book, no other man, Christian or Saracen, Mongol or pagan, has explored so much of the world as Messer Marco, son of Messer Niccolo Polo, great and noble citizen of the city of Venice.”

~Rustichello Di Pisa, The Travels of Marco Polo

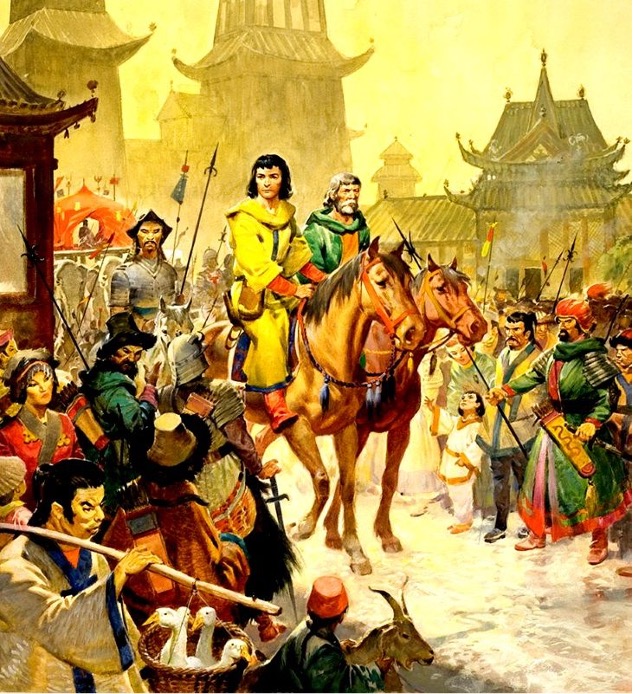

In continuing my examination of the remarkable adventures of the famous Venetian explorer, Marco Polo(1254-1324), it is important to note that my two-part series honors the 850 years since Polo launched his grand expedition from Europe through Asia in 1271. These adventures are explained in extensive and vivid detail in Marco Polo’s Biography—“The Travels of Marco Polo”, which provide first-hand details of the many unique encounters Polo had with the many cultures, exotic lands, peculiar customs, and warring conflicts during the time of his exploration. Part II of my book review will continue to shed light upon the expanse of the Mongol empire under Kublai Khan and the many conquests carried out by the ambitious Mongol Emperor who is so central to Polo’s explorative narrative.

Additionally, I will examine some of the more notable discoveries made during Polo’s quest, covering certain lands which he visited and some in which he passed by, yet provided descriptive accounts of the topography, people, animals, and other interesting factors which grant these locations their unique identities. Many such locations fall within various regions in China, coastal East Asia (including India, Japan, and Sri Lanka), and portions of the Middle East where Kublai Khan’s empire covered and imposed tributary obedience by the vassal nations beholden to him. The adventures which Marco Polo embarked on were conducted primarily on the basis of fulfilling special emissary missions on behalf of Kublai Khan. These missions were largely inspired by his first travels conducted under the instruction and training of his father Niccolo and uncle Maffeo, who had also explored China for years during Marco’s childhood.

Polo’s primary claim to fame was maintaining such an extensive account of his adventures through his book, “The Travels”, written in collaboration with artist and notable Romance writer Rustichello of Pisa whom he met during his exile in prison while in Genoa Italy in 1298. Rustichello most likely conveyed the oral accounts of Polo’s travels into writing. In an era before printing, it was perhaps the most notable published work by a traveler before the Age of Enlightenment, providing a fascinating and unprecedented glance of the many diverse societies, including their special customs, religious practices, and ways of life, which he encountered across the entire Asian continent. It was wildly popular and translated into many European languages during Polo’s lifetime.

With this recent commemoration of Christopher Columbus on Columbus Day earlier last week, many are unaware that much of the inspirations for Columbus to sail to the New World as a renowned explorer derived from him carrying a copy of the Travels as a means to emulate the celebrated adventures of Marco Polo, yet recent historical research now prove categorically that Christopher Columbus did not “discover” America, which was likely done first by the Viking explorer, Erik the Red (father of famous Viking explorer, Leif Erikson) in about 985 BC followed 300 years later by the great African explorer, Abubakari II.

Part II of my book review will divert somewhat from my initial essay in that it will examine several interesting stories in The Travels that were inspired by religious phenomena. Some legends depict the struggles of a Christian figure, such as the holy shoemaker, whose faith is challenged in some way by a domineering threat, such as the wicked Caliph of Baghdad, or a secular force imposing some sort of danger. I will begin with the tale of the shoemaker and shift into Polo’s travels in East Asia.

The Siege of Baghdad

After describing the land of Mosul, Marco Polo shifts his focus on the large city of Baghdad, Iraq, headed by the Caliph, Al-Mustaʿṣim, who governed all of the Saracens in the world, similar to how the Pope provided governance to all of the Catholics beyond his seat in Rome. Baghdad was known to possess many precious pearls that were imported from India by means of the Silk Road and sent among many Christian traders. Additionally, fine silks, woven fabrics, and the “greatest treasure of gold and silver and precious stones that ever belonged to a man” (Polo, 52), were attributed to belonging to the Caliph during the mid-13th century. Polo describes how the Caliph was besieged by an invasion conducted by Hulagu, the Great Khan over the Tartars (Turkic speaking peoples based primarily in central Russia). He was one of four brothers who ruled the Tartars, the eldest being Mongu.

Having conquered Cathay (northern China) and other surrounding countries, the four rulers were not satisfied until they attained total conquest of the world at large. Each of the brothers handled territory in a specific direction, with the lands to the south falling to Hulagu to conquer, which eventually brought him to Baghdad. Hulagu utilized a wise stratagem in Sun Tzu’s Art of War, which says to “appear weak when you are strong, and strong when you are weak”, by sending only a portion of his massive 100,000 cavalry to charge the gates of the city, while the rest of his forces were scattered on various sides in the woods to provide the appearance of weakness.

Al-Mustaʿṣim saw the measly forces at the gate and raised his flag to command his army to give chase to Hulagu’s men, who retreated into the surrounding forests. There, Hulagu’s other groups emerged and ambushed the Caliph’s men, crushing them in a well devised trap and successfully captured the city. Upon capturing the Caliph, Hulagu discovered a massive tower filled with gold, and questioned in amazement why the Caliph did not choose to provide a portion of this treasure to pay for hired soldiers to defend the city. This solicited only silence from Al-Mustaʿṣim, who was at a loss of words for his unpreparedness. Perceiving this to be a product of insatiable greed, Hulagu ordered that the Caliph be locked in his tower with no food or water, having only his vast treasure at his disposal. After four days, Al-Mustaʿṣim was discovered dead in the tower, and Polo noted him to be the last of the Caliphs since with the collapse of the Abbasid Empire.

The Tale of the Holy Shoemaker

In describing a miraculous story of a separate Caliph of Baghdad in 1225, Polo points to how he was very much opposed to the practice of Christianity and daily sought to devise ways to convert the Christians of his country into Saracens (basically Arab Muslims), or if proven unfeasible, opting to have them all killed. Having consulted with his advisers on this prospect, they discovered Biblical scripture spoken by Jesus in Matthew 17:20, which read that, “If you have faith as a mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move; and nothing will be impossible for you.” By this, the Caliph devised a means by which to test the Christians of his land, pointing to a nearby mountain by which he ordered them to move, or as consequence, suffer a terrible death, since he opined that if the Christians in Baghdad are unable to move the mountain, then they lack faith. He allowed for one to achieve this feat in ten days. This edict struck fear in the hearts of many Christians, but inspired faith in many that they would be delivered by the Lord from this impending demise.

Many prayed day and night to seek the Lord’s merciful protection from the Caliph’s wicked affront to the Christian faith. After 8 days passed, that an angel visited a certain bishop through a vision with the command to visit a one-eyed shoemaker in the region who would pray for the mountain to be moved out of its place. Marco Polo describes this shoemaker as a man who “committed no sin”, who fasted often, was chaste, and attended church every day, while giving away some of his daily bread for the sake of the Lord. There was only one cited instance of the shoemaker being prompted to sin, when he felt temptation after laying eyes upon a beautiful woman’s leg and foot upon assessing her shoe size. Upon knowing that he was tempted, he refused to sell the shoes to the woman and took out the one eye that looked upon her leg as penance for this sin. He was described as very holy and virtuous in this regard. When the bishop confronted the shoemaker to plead for his help in their dilemma against the Caliph, he was at first reluctant to help, doubting that he was good enough for the Lord to heed his prayer. But after coaxing the shoemaker, he eventually gave in to the pleas of the community.

On the final day of the grace period, there gathered a large assembly of over 100,000 individuals stationed before a large Cross. Many Saracens were in attendance, believing that the Christians would be unable to move the mountain and thus wanted to aid in facilitating their public execution. Fears and anxiety ran high among many of the Christians in attendance, and the stakes ran extremely high. When all were settled, the shoe-maker fell on his knees, lifting his hands in their air with a call to the divine Savior above to save the lives of the many Christians in Baghdad by allowing the mountain to be moved from its place. Upon finishing his prayer, he yelled, “In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, I command thee, mountain, by the virtue of the Holy Ghost, to depart thence” (Polo, pg. 56). Before the final words escaped from his mouth, the mountain began to crumble and shift from its place, inspiring profound shock in many. The Caliph and Saracens were especially at a loss for words and committed to becoming Christians; the Caliph keeping his conversion secret, and after his death, was buried with a cross around his neck. Though, when discovered, this prompted the Saracens to have him buried in a tomb apart from other Caliphs. Polo commemorates the triumph of the Christian faith and prayer of the shoe-maker as being a long-time celebrated story among the various sects of Christianity, including Nestorians, Armenians, and Jacobites.

Mongol Invasion of Japan

Prior to describing the merchant voyage from China to India, Polo provides an in-depth depiction of the coordinated attempt by the Mongol Empire to invade and conquer the island nation of Japan. Polo describes feudal Japan as a remote, large island 1,500 miles from the mainland of East Asia. He perceives the people to be “fair-complexioned” and “well-mannered”, and depicts the land as possessing a great abundance of gold, possessed in seemingly incalculable quantities. The palace of the Japanese Emperor apparently was roofed entirely in fine gold, in addition to hallways, windows, and the chambers all being adorned in gold, with an appraisal value exceedingly beyond measure. Additionally, the island possesses ample supplies of red pearls and various other precious stones. When word of Japan’s vast riches reached the hearing of Kublai Khan, he made the resolve to conquer the entire island for the benefit of his expanding empire, having recently conquered and forced nearby Korea (Goryeo) to become a vassal state. He sent out two of his barons, Zaito and Kinsai, who commanded many large ships carrying infantry and cavalry. They were notoriously jealous of one another, and neither would lend assistance to help the other out if required.

Upon landing on one of the islands surrounding Japan in 1268, they were blindsided by an incoming gale from the north which carried heavy winds that caused many of their ships to collide as they were departing from the island. Those ships that weren’t closely jammed together were able to pass through the wreck and escaped to open sea, later returning to the island after the storm abated to rescue the numerous survivors. The ships collected as many of the survivors as possible and were forced to leave nearly 30,000 men on the island. Believing themselves to be abandoned to a potentially cruel fate, the men sought refuge, fearful for their lives in what was an unknown environment with no available means of escape. Word reached the Japanese emperor of the mainland, who was overjoyed to learn of the destruction of the invading Mongol armada and subsequent plight of the survivors of the wreck on the nearby island.

The Japanese ruler sent out a fleet of ships to capture the stranded Mongols, only to find that upon making landfall, the men had escaped to the opposite side of the island. While the Japanese samurai gave chase to the enemy, the Mongols took a surprise detour and encircled the completely unguarded Japanese ships and easily boarded them. Hoisting the sails of the enemy, they crossed over to another nearby island off the coast of Japan and were welcomed in under the mistaken assumption that the arriving men belonged to the ruler. Upon entering the island as a Trojan Horse, the invaders besieged the capital city, driving out the predominately older citizens aside from the attractive young women who were kept as hostage. Upon the ruler of the island learning of the loss of the capital, he and his followers were mortified, and launched a counter-strike on the city.

The Great Khan’s men held the city for nearly seven months straight as the Japanese attacked their near impregnable defenses from all sides. This, while the Mongols attempted to find some means of sending word to Kublai Khan for reinforcements, all to no avail. Finding no way of making contact, the 30,000 Mongols eventually came to terms by surrendering to the Japanese, on the condition that their lives were spared and that they remained on the island for the rest of their lives. Upon learning how terribly the expedition to conquer Japan went, Kublai Khan executed immediate judgment upon his two barons who oversaw the disastrous initial invaison— he had one of them beheaded and the other exiled to the desolate island of Zorza. There, his hands were wrapped in flayed Buffalo skin, which trapped the hands in a gradual shrinking process as it dried, leaving him to die helpless on an island with no access to food.

The invasion of the islands surrounding Japan described by Marco Polo in the Travels appears to predate the official invasions of the Japanese mainland launched by the Mongols in 1274 and 1281. These attempts to invade were orchestrated under Kublai Khan, after twice sending emissaries in 1266 and 1268 to coerce the reigning Shogun, Hojo Tokimune, to allow Japan to serve as a vassal state to the Mongol Empire. The Great Khan was ultimately unsuccessful in what was a mighty attempt to invade and conquer Japan. In the first invasion attempt in 1274, the Mongols committed an upward of 700-800 ships, including those commanded by Korean, and Chinese mercenaries, while commanding a total of 23,000 ground troops, compared to the 10,000 Japanese Samurai. The second attempt in 1281 saw 4,400 ships and 100,000 ground troops among the combined Mongols, Koreans, and Chinese forces, against the estimated 40,000 Japanese men. Much of the Mongol’s defeat came through the violent storms that caused them to lose up to 75% of their troops and supplies during both of the invasions, with many men and collapse ships swallowed up by the violent ocean currents as a result. Prior to America’s occupation of Japan following the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the Second World War, the Mongol invasions were remarkably the closest Japan had come to being conquered as a nation in the last 1,500 years.

The Legacy of Marco Polo’s Infamous Travels

Marco Polo’s extensive and elaborately exceptional adventures laid the groundwork for many future European expedition, inspiring a host of big-name conquistadors and explorers alike. These include Hernan Cortes, Amerigo Vespucci, Vasco Da Gama, and most importantly Christopher Columbus. Part II of my article sought to highlight some the perceptions of Polo’s quest in the East Asian region, particularly Japan, and underscore many of the examinations he made about the ever-expanding Mongol Empire stretching far beyond the successful conquests of Cathay (north China) and Manzi (south China) and into surrounding nations like Goryeo (Korea) and neighboring Japanese islands. As mightily successful of a warlord that Kublai Khan was, even he was unable to subdue and properly invade feudal Japan during his several campaigns.

Marco Polo’s The Travels provides a unique insight into an often-underrated campaign launched by the Great Khan to invade the surrounding islands of Japan, prior to his official attempt to invade the mainland of Japan, which often goes unnoticed in various historical accounts of the time. Part II also highlighted the militaristic campaigns of other rival khans, such as Hulagu Khan, who ruled over the Tartars and lead a successful conquest of the Caliph, Al-Mustaʿṣim, forces in Baghdad. And similar to Part I, I examined one of the featured fantastical tales, some fictional and others based on real accounts, that Polo recounts of interesting battles, military coups, and the triumphs of Christianity over secularism—as portrayed in the story of the Holy Shoemaker and the formerly wicked Caliph who later became a born-again Christian.

My concluding essay on Polo also holds a significance on what appears to be the modern-day assault on once celebrated European explorers, who pioneered their way across the New World and brought forth ingenuity, precious resources, religious enlightenment, and a host of other beneficial contributions that fostered the development of the formerly uncivilized, unexplored regions of North and South America. These Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese explorers, many of whom were greatly inspired by the remarkable quests lead by Marco Polo, laid the groundwork for establishing the Americas into the developed and industrious hub for European commerce and trade, sprawling with a reservoir of renowned opportunities to be realized generations into the future. But for today’s children learning about the history of the conquistadors and Christopher Columbus, the legacy of these men is often tarnished by the revisionist historical portrayal which paints them as “evil white men” who killed and stole the land of the “innocent” Native peoples already established in the Americas. Thankfully, Republican Governors like Ron De Santis of Florida, proposed a Columbus Day proclamation to honor the incredible explorative achievements of Christopher Columbus, who (after Erik the Red & Abubakari II) eventually paved the path for the civilized development of the North American continent by means of enlightened Western ideals of Christianity, exploitation of its vast natural resources, and culture.

De Santis hit against the cancel culture wave that is inspiring a rebuke toward Columbus in American public schools, in addition to an embrace of baseless unofficial celebratory replacements such as “indigenous peoples day”, stating, “Individuals who seek to defame Columbus and try to expunge the day from our civic calendar do so as part of a mission to portray the United States and Western history in a negative light as they seek to blame our country and its values for all that is evil in the world, rather than see it as a force for good.” Renowned explorers like Columbus, Cortes, and Polo should be venerated for their significant contributions to global exploration and discovery, not attacked for misconceived notions of abuse to native peoples—most of whom were initially hostile and violent toward incoming travelers—or ignored for the monumental groundwork they laid forth in establishing the Americas during the golden Age of Exploration.

*N.B: This essay is based in part on a synopsis of Marco Polo’s seminal work, The Travels of Marco Polo(1300), the reissue edition published by Penguin Classics (September 30th, 1958).

Category: Socrates Corner